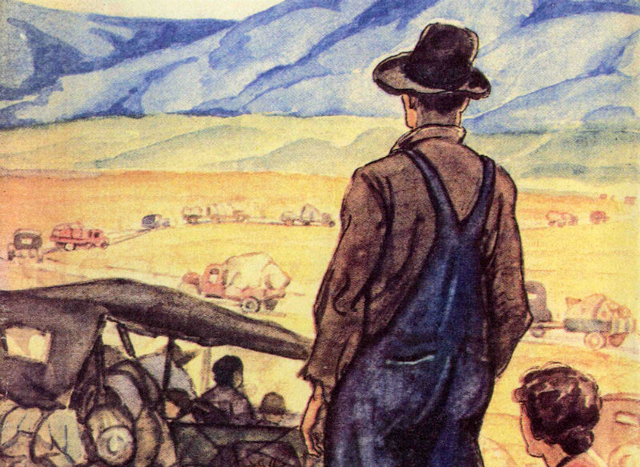

The 1930’s and 40’s was a time of turbulent upheaval for society; something that even today we still feel the ripples of. The 1930’s were defined by the economic collapse of the Great Depression, which ushered in an era of the New Deal reforms that reshaped America’s domestic policy. And if that was not enough for one generation to go through, the Depression was followed up with World War II, the bloodiest conflict of the 20th Century. This was an era that offered up so many stories of survival in the face of adversity and there were plenty of writers who managed to capture that era with a genuine emotional connection to the times. One such author was American crime novelist James M. Cain. Cain, a former journalist, was known for creating hard-boiled stories of dark corners of the American experience. His novels were often first person confessionals of his characters admitting their crimes to the reader and giving out all the details about how they were done. His stories often involved murder, love affairs, and deception as part of their plots, which made many of his earliest works particularly intriguing to readers looking for something salacious to read in the turbulent Depression years. The hard-edged stories that he wrote particularly caught the eye of Hollywood. Many of his early novels, like The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity would not only receive high profile movie adaptations, but Cain’s work would also be instrumental in developing a brand new film genre that would come to define the era, known as Film Noir. And while many of his stories fit well into the genre of Film Noir, not every story that he wrote necessarily centered around crime either. In perhaps his most well known novel, the 1941 best-seller Mildred Pierce, his story there would actually center around social and economical disparity resulting from the Great Depression. In a rather ahead of it’s time sort of way, Cain actually shun a spotlight on the struggles of women in the workplace and created a surprisingly potent feminist figure in his titular protagonist; a woman who manages to overcome the obstacles put upon women seeking success in American society.

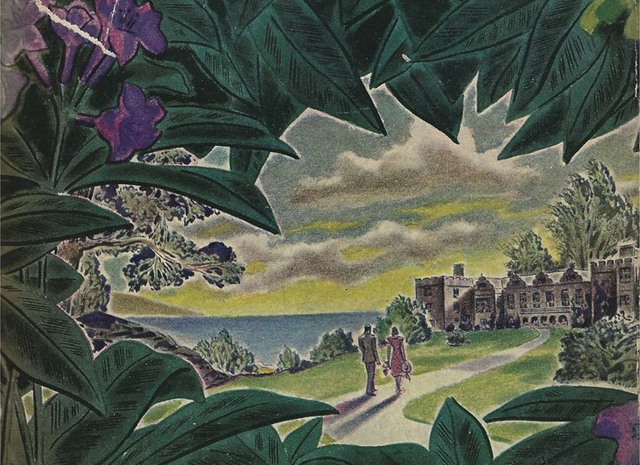

It didn’t take long for Hollywood to see the potential in Cain’s story, and Warner Brothers immediately snatched up the rights to the novel, intending for it to be one of their next prestige films. Micheal Curtiz, fresh off of his Oscar winning success directing Casablanca (1943) would prove to be an ideal choice in bringing this film to the big screen. He was a multifaceted filmmaker who could work in any kind of genre, including crime thrillers like Angels With Dirty Faces (1938) starring James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart. But what mattered even more was who would be playing Mildred. This was a role that was surprisingly not sought after by most actresses at the time, because many stars were afraid of taking on a motherly role because that was a sign of an actress getting older, which would have aged them out of other coveted roles. Michael Curtiz’s preferred choice for the role, Barbara Stanwyck declined for this very reason, as did Bette Davis, which is ironic given who they did eventually cast. Thankfully for Warner Brothers, there was one movie star that not only was unafraid of taking on the role of a mother in her film, but was also actively campaigning herself for the part as well. Joan Crawford was very different from a lot of other leading ladies of her time. She often shunned glamour roles, even though she was stunningly beautiful enough to pull them off, because she was more interested in taking more risk taking parts that were often grittier and truer to the American experience, especially during the depression. Mildred Pierce was a role that seemed almost tailor made for her. She was drawn to working class heroines, and she had the acting chops to pull it off, while at the same time having the matinee idol visage to still shine on the big screen. And this would be a role that she would make all hers. The film would win Joan the only Academy Award of her career, and it’s still the role that most people associate her with. It can definitely be said that Curtiz and Crawford delivered a cinematic classic with Mildred Pierce (1945), but it is interesting comparing it to the book as well, because there are some striking differences. Some of them were done out of necessity, due to the code censorship of the day, but it does make watching the movie a slightly different experience than reading the novel. And in a surprising twist, some of the changes made may have inadvertently contributed to the birth of the film language of Film Noir as a result.

“I felt as though I’d been born in a kitchen and lived there all my life, except for the few hours it took to get married.”

One thing that becomes pretty clear between reading the book and watching the movie is that their depictions of Mildred vary in subtle ways. The book treats Mildred as a more grounded depiction of a women driven to survive in any way she can. She’s not glamourous or stunning; she’s an average woman both physically and mentally. And that’s what made her a relatable heroine. Many readers recognized her, or perhaps found themselves feeling seen as her. This was a woman who had to sacrifice a lot to maintain everything that she could of the life she had before things went haywire. She was the embodiment of the average American who had to scrape by in the midst of the Depression and also had to step up when the War left the nation with even less stability. Her adversity through it all is what made her such a potent symbol of the time. She goes from housewife, to waitress, to restauranteur, to a corporate head in a very short span, which before the Depression years would have been seen as unusual for a woman. But this was also the Rosie the Riveter era, when women were called upon to enter the workforce in a way that they hadn’t before because so many men were overseas fighting in the War. It was a time when women were finally showing their worth as equals in the workforce, and Mildred Pierce was that type of upwardly mobile heroine that this time period valued. It’s probably what drew Joan Crawford to the role, because she wanted to represent that kind of figure of feminine exceptionalism. And for the most part she does do justice to the character of Mildred. She shows off how intelligent Mildred is at running a business and finding new ways to succeed that some of her male counterparts would never have figured out. The one big difference in her performance is that her Mildred is a bit more melodramatic, which is probably a result of the acting style of the time. Crawford was definitely more subtle in her acting than most, but there is a soap opera like quality to her performance her as well.

“I think I’m really seeing you for the first time in my life. And you’re cheap and horrible.”

One thing that the movie does perfectly translate over from the book is the theme about the corrupting influence of wealth. In particular, both the movie and the book are sharply critical of elitist attitudes in society. Living through a Depression would have soured many people’s attitudes towards those who flaunted their wealth, especially if they were people who never earned their money through hard work. This attitude is personified through two different characters in the story; Mildred’s deceptive second husband Monty, and her snobbish oldest child Veda. Veda in particular is one of the most loathsome characters ever created in both literature and on the silver screen; a spoiled brat who will do anything to maintain an affluent lifestyle, even at the cost of shaming her own mother. She makes for a shocking villainess in this story given the lengths she goes to. In the movie, she was played by a remarkable young actress named Ann Blyth, who as of this writing is still with us today at the ripe old age of 97. Blyth does an amazing job of personifying this cold, ruthless schemer who will never accept anything less than what she feels like she’s owed; which is mostly unreasonable. She is the biggest test ever of a mother’s unconditional love and the tragedy of Mildred’s story is that she puts the love of her children before everything else. In the movie, you see Mildred have more of a spine when standing up to her daughter, including one of cinema’s most epic slaps to the face after Veda shames her for working as a waitress. Mildred’s confrontation with her daughter builds more gradually in the novel, with Mildred putting up with a lot before things hit their boiling point, which results in a very shocking moment in the book. For a lot of people who read the book and watched the movie in it’s era, Veda was the personification of the very class of people who made the Depression as trying as it was; unchecked greed mixed with a stubbornness to refuse to change for the sake of others.

The characters of Mildred and Veda very much translated in tact from the book to the screen, but a lot of other characters saw more dramatic changes in the adaptation. Mildred’s first husband Bert is a bit different in the movie, especially in the opening. You see him as a bit more of a negative influence in her life as he becomes more frustrated that Mildred is pulling her wait more than he is. Bert (played by Bruce Bennett) is definitely a symbol of the displaced man who ended up loosing his social balance through the Depression. Without work, a lot of men couldn’t support their families, and that led to a lot of broken marriages as families split so that there would be one less mouth to feed in the household. But, like Bert in the book, the portrayal of the character softens as he recognizes Mildred’s value as a successful businesswoman. Though they do go through with the divorce, it is revealed that Bert is the better man in her life as the scheming Monty shows his true colors through the latter half of the story. It’s interesting that the movie chooses to put Bert in a more antagonistic role early on than how he’s portrayed in the book, which is far more positive. It’s perhaps the movie’s way of motivating Mildred to push herself harder to prove everyone else is wrong about her. Another interesting change from the book is the absence of Mildred’s neighbor and closest friend, Lucy Gessler. In the book, Lucy is a feisty and loyal confidant for Mildred who helps to push her in the right direction; appealing to all of her better instincts. The movie instead gives a lot of Lucy’s characteristics to another character from the book, Ida Corwin, who starts off as Mildred’s supervisor at a restaurant and then later becomes her business partner. Ida in the movie is played by a scene stealing Eve Arden who gets all the best one-liners in the movie. It seems like the filmmakers wanted to streamline the story by combining the two characters into one, but it was probably also done as a means of giving Mildred more agency in the earliest part of the story. If she only acted upon pursuing a career in the restaurant industry after a friends suggestion, then it minimizes the self actualization and deep rooted intelligence of Mildred herself.

“Veda’s convinced me that alligators have the right idea. They eat their young.”

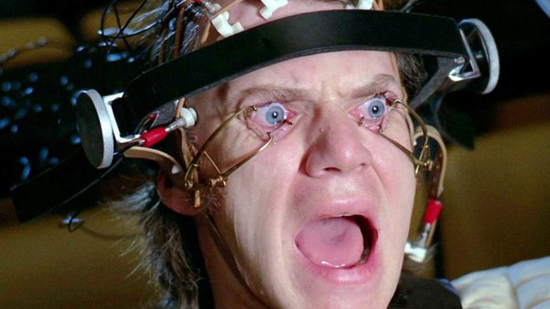

Where the book and the novel divert the most though is the framing of the entire story itself. Oddly enough, of all of James M. Cain’s earliest novels, Mildred Pierce was the only one that was not framed as a first person testimonial. And yet, that’s the way that the movie chooses to frame it’s story, having Mildred herself recount all the events that led up to this particular night as she’s being interrogated by the police. Which is the other big change from the novel; there’s a murder in the movie. The murder is literally what opens the movie, with Monty (played by Zachary Scott) falling dead from a gunshot, his last words being Mildred’s name. We don’t see who fired the shot, but the very next moment in the movie shows Mildred walking onto a pier, contemplating throwing herself in and committing suicide, which is certainly a suspicious thing to do right after we’ve seen her husband be murdered. All of this, however is an invention purely for the movie itself. The whodunit aspect of the movie in a way was done as a response of skirting around the aspects of the book that couldn’t be adapted because of the Production Code in place at the time. In the book, there is a much different and more shocking conclusion to the story. Mildred has given up so much of her hard earned wealth to help give Veda and her new husband Monty the lavish lifestyle that they clearly cherish more than anything. But, it puts Mildred in a needlessly precarious position with her business expenses being unable to pay for all of this luxury living. And then she is dealt the harshest blow of all when she finds Monty in bed with Veda (who by the way is still underage). Monty desperate to plead his case, but Veda just arrogantly flaunts the scandalous situation even more in front of Mildred, and this becomes the final straw. Mildred violently attacks Veda and strangles her, causing her to lose her beautiful singing voice. There’s no murder, but what was left of Mildred’s idealized life with Veda and Monty is forever broken. What’s more, it also proves to be another scam on Veda’s part, as pretending to lose her voice merely lets her out of a contract that kept her in California. She leaves Mildred broken even further by this deception and in a way still gets what she desired by the end. The book’s finale has Mildred consoled by Bert in her grief, and ultimately Mildred celebrates by proclaiming “The hell with her” before the two decide to drink their sorrows away.

This bittersweet ending that comes after the villain leaves without ever facing their comeuppance would not have flown with the censors in Hollywood at the time. The bad guys always had to pay the price in the end no matter what, so that’s why the murder plot was set up in the film. The set up is the same; Mildred doesn’t find Monty and Veda in bed together, but she does see them in a compromising intimate situation, which still gets the betrayal across in the story. Where things divert is that Monty second guesses his relationship with Veda after Mildred has found them out, and Veda can’t accept that, so she shoots Monty dead for betraying her. Mildred returns after hearing the gunshots, prepares to turn her daughter in to the cops because of how hurt she is by their affair behind her back, but Veda once again plays upon Mildred’s motherly love and Mildred, in another moment of weakness, tries to take the blame for her daughter’s crime. Only, it doesn’t work out and Veda is still arrested. Mildred is finally free of her, but the movie leaves Mildred still heartbroken, which is different from the more optimistic finale in the book. The themes of the book still work within this new finale, but it also undermines Mildred’s growth as well. You just want her to finally assert herself as a mother finally after Veda clearly crossed the line, and yet she still puts her above herself. If there was ever a warranted place for Mildred to actually be justified in abandoning her child, this would’ve been it. But, that’s what the filmmakers had to deal with if they were going to make this story work under the Code restrictions. And in some ways it was a blessing in disguise. There’s nothing noirish about the original book, but the murder plot in this movie helped to make it work within the Noir style. Curtiz and his team made great use of dramatic lighting and shadows in this film to give the story a darker tone. The ending in particular, with Mildred finding Monty and Veda making out in the beach house is one of the most quintessential Noir moments ever pt on film. While most of the rest of the movie is a compelling drama about endurance and adversity in the face of ongoing struggles, the noir scenes that frame it are just as potent as any detective story made around the same time that were more distinctly noirish. In fact, you can see the influence of Mildred Pierce in many other Noir films that came after; the pier scene being an often imitated moment in other films.

“Mildred…We weren’t expecting you. Obviously.”

One thing that this movie for sure did was to give Joan Crawford the iconic role that would define her career. There’s questions about whether she was as good of a mother in real life as she was playing Mildred Pierce, as Mommie Dearest (1980) famously speculated on. But there is no doubt that she crafted a potent portrayal of motherhood that in many ways was both inspiring and also frustrating. The book gives a much more satisfying catharsis for Mildred, as she finally learns to let go and just accept that she is better off without toxic people like Veda and Monty in her life. The movie sadly still confines Mildred into a sense of guilt by the end that she honestly doesn’t deserve. But overall, the book and the movie are undeniable classics that still hold up very well 80 years later. The movie stands as one of the classics of old Hollywood, with incredible craft behind the camera as well as in front by it’s incredible cast of actors. One can’t help but think of Joan Crawford in that iconic fur coat standing on the pier in the dead of night as a quintessential Hollywood moment in cinema. And the fireworks between her and young Ann Blyth are some incredibly intense scenes as well that further define this as a great film. The book on the other hand goes far deeper into the character’s psyches and also takes more risks in telling it’s story. Many years later, director Todd Haynes made his own adaptation of the novel in a 2011 mini-series for HBO, starring Kate Winslet as Mildred and Evan Rachel Wood as Veda. In that series, Haynes stuck much closer to the book and was able to delve more into the darker themes of the story, given the extra creative freedom he had with no more Production Code to get in the way. The mini-series is pretty good in it’s own right, but the 1945 film feels even grander because of it’s iconic old Hollywood status as well and also because it was more of a snapshot of that time period. Mildred Pierce spoke to a world that was just coming out of 15 of the worst years this country has ever faced with the Depression and the War. Those who participated in the movie lived through all that, and that made their portrayals in the film all the more personal. As we are going through our own time of uncertainty right now, I wonder how audiences today would respond to a story like Mildred Pierce. In many ways, I think a character like her would still feel familiar to a lot of people and that’s what helps to make her portrayals on the page and on the big screen feel so timeless.

“You look down on me, because I work for a living. Don’t you.”