There are a number of animators who manage to rise up to the ranks of directors that become household names. Today, you see the likes of Brad Bird, Chris Sanders, Pete Doctor, or the team of Christopher Miller and Phil Lord become well known in the film industry beyond just the field of animation. But for the longest time, being an animation director was not much of a step above just being an animator. The early days of animation often left the director’s name out of the credits of the cartoons that ran in theaters alongside feature films, and the only name associated with the shorts were the names of the people who own the studios that made them. When you saw a short cartoon, you would be seeing a Disney Cartoon, or a Fleischer Cartoon. Warner Brothers didn’t even have a name attached to their shorts, just calling them Looney Tunes or Merry Melodies instead. It was only in the post-War years where animation directors were given more credit, but even still, they were known mostly just to animation aficionados. Chuck Jones emerged out of the Looney Tunes shorts factory to carve out his own name in animation, particularly with his work on the holiday short How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1966). Wolfgang Reitherman, one of Walt Disney’s treasured Nine Old Men, would take the reigns of animation at the studio, directing most of the features at Disney after Walt’s death, from The Jungle Book (1967) to The Rescuers (1977). And of course, Richard Williams was becoming a legend in the animation world for a movie he would never finish called The Thief and the Cobbler. But, household named directors from the animation world has been a relatively new thing, and even in this case, it’s still a rarity. An animation director that you can really point out as the person who helped to break through and make a name for himself both in animation and in Hollywood in general was an ambitious animation pioneer named Don Bluth.

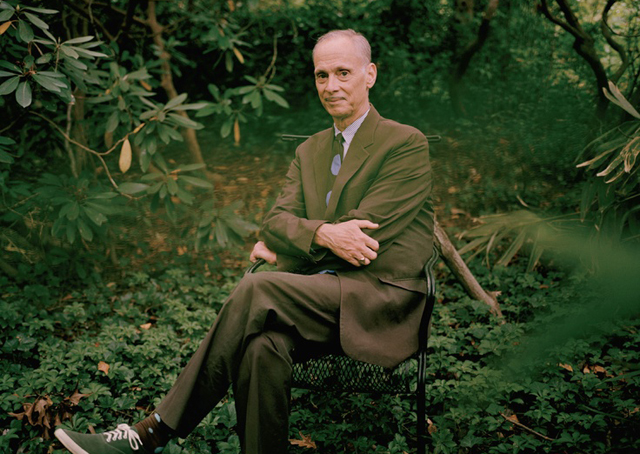

Don Bluth began his animation career right out of college working as an inbetweener at Disney. After a couple years, he was made an assistant animator for Disney Nine Old Man legend John Lounsbery and he got to contribute to the animation of movies like Sleeping Beauty (1959). He left Disney not long after that to go on a mission for the Morman Church, and after that he did a lot of freelance work as a layout artist for Filmation. In 1971, he returned to Disney to work alongside his old colleague John Lounsbery on films such as Robin Hood (1973) and The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1977). He was promoted to directing animator The Rescuers, and many believed that with the upcoming retirements of the aging Nine Old Men that Bluth would be one of the heirs to the Disney Animation studio now that the old guard was leaving. Sadly, his mentor John Lounsbery also passed away suddenly during this time. Bluth was also butting heads with the higher ups at Disney, voicing his displeasure at their lack of creativity during the post-Disney years and relying on safe projects like Pete’s Dragon (1978). While Bluth was working on the Nativity themed short, The Small One (1978), him and a team of his fellow Disney animators were covertly working on a secret independent project called Banjo, The Woodpile Cat (1979). Disney was not happy with Bluth’s independent work, and Bluth decided that his time at the Disney Studio was over. He quit and took a huge chunk of the Disney Animation staff with him, leaving Disney’s animation department devastated. Bluth, along with his key cohorts Gary Goldman and John Pomeroy, established Don Bluth Productions and they began work on their first feature as an independent studio, called The Secret of NIMH (1982). Eventually getting released by MGM, NIMH was a huge success for Bluth and established him as rising star in animation. Soon after, Steven Spielberg became interested in working with Bluth, and he signed with Amblin Productions for a two film deal, making An American Tail (1986) and The Land Before Time (1988). It was an opportune time for him, with his rise and Disney’s struggles with The Black Cauldron (1985). It looked like Bluth would soon become the biggest name in animation since Walt himself. And then something changed. After All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989), Bluth’s track record got spotty just as Disney was beginning their Renaissance. He got a second chance in the late 90’s with a new set up at 20th Century Fox, making the ambitious musical fantasy Anastasia (1997) but even this was short lived as the studio closed after the failure of Titan A.E. (2000). Bluth hasn’t directed a feature since. Below is a look at the different spotlights of his animation style and a career, and how they continue to define him as a key figure in animation.

1.

DARKER THEMES IN FAMILY ENTERTAINMENT

Of all the things that drove Don Bluth away from Disney it was perhaps his belief that the studio had abandoned it’s roots that became the biggest area of contention. Bluth believed that Disney should’ve been taking bigger risks in the post-Walt years, citing the way that Disney’s earliest films were bigger gambles than the play-it-safe films that they were making at the time. In particular, he believed that animation shouldn’t be afraid to tackle darker themes and tones. Disney’s earliest movies all had moments that were much darker and sometimes terrifying, such as “Night on Bald Mountain” in Fantasia (1940) or the Pleasure Island sequence in Pinocchio (1940). With Disney making films like The Aristocats (1970) and The Rescuers (1977), it was clear that they were retreating away from scary moments and were catering to a much younger crowd. For Bluth, he believed that there was a way to make animation darker and more mature without alienating family audiences. The very first film he worked on, The Secret of NIMH, is perhaps the best illustration of his mission statement. The film is harrowing and at times violent, but it still maintains a sense of enchantment that young children could still be invested in, and it had it’s own colorful cast of animal characters to keep the story whimsical too. The slate of films Don Bluth made during the 80’s in many ways continued this blend of family friendly warmth spiced with a hint of danger and at times scary imagery. But, also Bluth was also not afraid of bringing in a bit of tragic consequences into his stories as well; something he took inspiration from in early Disney movies. It’s undeniable that the death of Littlefoot’s mother in The Land Before Time was inspired by the similar loss of a parent in Disney’s Bambi (1942), and it also may have later inspired a similar moment in Disney’s own The Lion King (1994). It was this commitment to bringing animation back to it’s riskier roots that helped to distinguish Don Bluth’s movies from those of other animation studios. It’s kind of ironic that at the same time Bluth was flourishing with his darker themed movies that Disney tried to do the same with their film The Black Cauldron, and they failed miserably. It was definitely a power shift in animation that no one had expected.

2.

HIGHLY EXPRESSIVE ANIMATION

Don Bluth is one of the animation icons with a very unique way of drawing movement into his characters. You can see it’s beginning in some of his work at Disney, with characters like Elliot the Dragon in Pete’s Dragon, where he animates his characters with a lot of expressive movement, particularly with the mouths. The lip flaps of his characters are distinctively exaggerated, which at times can look a little strange. You don’t get a lot of subtlety in his character animation, and that’s not entirely a bad thing. It’s yet another element that sets his movies apart from those of Disney and other studios, as every character in his films are all drawn in that distinctive Don Bluth way. But, even minus the subtlety, the characters that he does bring to life make up for all that with enormous personality. Fivel from An American Tail for instance stands out with that highly expressive animation because it fits with his personality as a restless child. The manic expressions he animates also work well with some of the physical comedy, particularly in a movie like All Dogs Go to Heaven which has a lot of slapstick moments. But, when he needs to bring more emotion to a scene, his team can deliver that as well. There are some truly heartbreaking moments in An American Tail and The Land Before Time that Bluth’s animation definitely manages to nail down. Unfortunately over time, his films would lose some of that manic spontaneity and become more complacent as he tried to attempt more natural animation in an attempt to catch up to Disney during their Renaissance. Thumbelina (1995) featured the least exaggerated animation of his filmography, and of course it is the dullest movie he ever made. He also attempted subtlety with Anastasia (1997), but at least it was more balanced with a more substantial budget and some more creative freedom used on the less subtle animation of the villain Rasputin. Still, the Don Bluth style of animation is truly unique and unlike any other style found in animation anywhere else.

3.

EMBRACE OF THE BIZARRE AND RANDOM

One tradition in animation that Bluth continued to hold onto in his films was the use of songs to tell his story. The Secret of NIMH avoided musical numbers, but An American Tail fully embraced the trope, and the majority of his films since also continued to act as musicals; the exceptions being The Land Before Time and Titan A.E. But it’s in these musical numbers that we see Don Bluth really branch out into some surreal territory. In a sense, this is another thing that he was inspired by early Disney, as he seemed to particularly be drawn to the weird and over the top musical sequences that some of those early films would delve into every now and then. In particular, I think he was deeply influenced by the “Pink Elephants” sequence in Dumbo (1941), and it’s surreal dreamlike presentation. All Dogs Go to Heaven in particular has some of the oddest musical sequences found in any animated movie. Set aside that he had actor Burt Reynolds do his own singing as the main character Charlie (a strange choice on it’s own), but the movie stops dead in it’s tracks halfway through the film so that there can be a Busby Berkeley style musical number with a giant, big-lipped singing alligator (voiced by the late great Ken Page of Oogie Boogie fame). And beyond that strange musical sequence, Bluth seemed to follow that up with a whole movie based around random musical sequences called Rock-a-Doodle (1991). Even in the more straightforward Anastasia you get a musical sequence like the villain song “In the Dark of the Night” where Bluth is able to let things get a little strange for a bit. There’s something definitely appealing about how his movies don’t have to follow a logical path, because animation allows for creative flights of fantasy to take place. For some of the greatest random creativity seen in any Bluth animation though, the best place is to find it is not on the big screen but rather the arcade. Bluth was a pioneer in video gaming as well as in cinematic animation with the creation of the Laserdisc based Dragon’s Lair (1983) and Space Ace (1983) video games. These fully animated playable movies feature some of the most insanely bizarre animation that Don Bluth’s studio ever made, and they are truly something wonderful to behold.

4.

CONTEMPORARY FANTASY

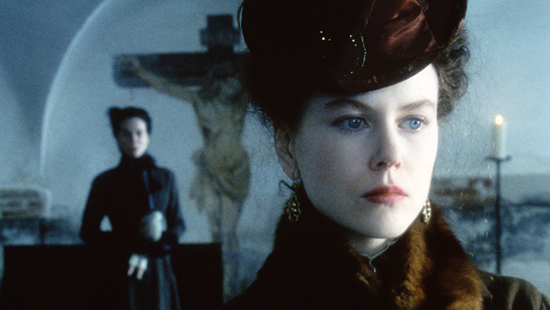

One of the common threads in Don Bluth’s movies is the presence of magic found in the present, or near present day. Unlike Disney films that relied on adaptations of well known (and public domain) fairy tales dating back to their very beginning with the likes of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), Bluth’s movies were mostly original stories, or based on a recent YA novel like The Secret of NIMH. Even with the more contemporary settings, his movies are still filled with magical elements that take advantage of the limitless potential of the animated medium. All Dogs Go to Heaven literally has the manifestations of Heaven and Hell brought to life in the story, with Hell being especially terrifyingly realized in the infamous “Charlie’s Nightmare” sequence found in the movie. Magic also plays a significant part of Rock-a-Doodle, with a live action human boy named Edmond being transformed into an animated kitty cat by a sorcerer owl named the Duke (voiced by Christopher Plummer), in one of the many bizarre elements of that movie. You even have the cross section of magic and real world events play out in Anastasia, with the Russian Revolution getting an assist from a magical curse cast by Rasputin on the Romanov family. Quite a few of Bluth’s movies take on these fantasy elements, even in grounded films like An American Tail, where a storm at sea even takes on the appearance of a monster at one point. But, only in one case did he ever attempt to adapt a known fairy tale, the aforementioned Thumbelina. For the most part, he uses magic as a way of giving his own original story ideas a more inventive element that allows for more flights of fantasy in animation. Sometimes it works to the movies’ benefit, like the imaginative All Dogs Go to Heaven or the bizarrely fascinating Rock-a-Doodle. But then there is the film A Troll in Central Park where the fantasy feels a bit lazy. Even still, it’s clear that Don Bluth found it essential for his movies to have a good amount of magic within their stories, and it often made his films that much more entertaining.

5.

JOURNEYS OF SELF-DISCOVERY

One other story element that Don Bluth would include as a part of his movies is the journey towards self-discovery for his characters. In most of his movies, his character set out for a destination or goal, and in the process gain a further understanding of who they are and how powerful they can be. This is something that especially defines the story of Mrs. Brisby, the main heroine of The Secret of NIMH, who goes from a concerned mother trying to protect her children to wielding a powerful magical force by the film’s end, something that she never realized she was capable of until she had no other choice but to act. For some of his main characters, he sends them on literal journeys. Fivel becomes separated from his family and must navigate his way through his new home in America in order to find them again. The Land Before Time sends the orphaned Littlefoot on a journey to find the Great Valley and along the way he meets other stranded misfits like himself who must rely upon each other in order to survive, and in the process, they become an inseperable unit themselves. For these characters, they are coming of age stories, as the young protagonists must learn to grow up fast in order to survive on their own. For the character of Anastasia, she literally is on a “Journey to the Past” to rediscover who she was before she lost her memories of childhood, which might connect her to being the long lost Romanov princess. But you also see these self discovery journeys happen in a reverse direction, where a scoundrel like Charlie in All Dogs Go to Heaven begins to change his ways after literally having a brush with Death. The reason why Don Bluth seems drawn to these kinds of stories is because they are always a valuable way of building his characters. The best animated movies always involve the character wanting to have something, which is something that definitely defined the films of Disney’s Renaissance. But for Bluth’s movies, it ties back to his attraction to darker themes in his films, as he sets out to really put his characters through the wringer. His characters must go through a lot of darkness before they see the light, and for the most part that journey will inevitably change them. Littlefoot becomes a leader by the end of his ordeal. Fivel, much wiser and closer to his family. And Charlie learns the meaning of sacrifice and acceptance of his ultimate fate. For a lot of young animation fans that grew up on his movies, we still look at his movies as some of the most enriching and life-affirming tales ever put into animated life.

It’s unfortunate that Don Bluth wasn’t able to sustain the momentum that he had during his early years as an independent animation director. That run of the 1980’s is still iconic to a generation of animation fans. It’s strange that he only partnered with Spielberg for just those two films, An American Tail and The Land Before Time. There’s never been an explanation for why they fell out of that partnership, but had he stayed at Amblin beyond those films, who knows how different the animation landscape would have been in the years that followed. Bluth might have been able to sustain his creative output in the renewed competition he faced during the 1990’s with the Disney Renaissance. Strangely enough, his abrupt departure from Disney may have actually benefitted Disney more in the long run, because when he took a whole generation of animators with him, it was the new recruits just out of CalArts that stepped up to take the reigns of Disney Animation. The young and eager to show what they were made of animators at Disney soon put a ton of new creative effort into movies like The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994), which would change the animation landscape even more than what Don Bluth was doing. Throughout the 1990’s, it was Bluth that was having to play catch-up, and the quality of his films unfortunately suffered. Then came the new threat of computer animation pioneered by Pixar, which a traditionalist animator like Don Bluth had no answer to. Titan A.E. was an attempt to bridge both worlds, with hand drawn characters existing in computer animated environments, but it’s an experiment that didn’t pan out. Since then, Bluth has retreated mostly out of the animation industry as a whole. With his studio closed, he has since only done small commissioned projects, such as the short The Gift of the Hoopoe (2009), made for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He did launch a Kickstarter campaign with his longtime producer Gary Goldman to get a new animated feature based on the game Dragon’s Lair made, but sadly even after reaching his initial funding goal, not much movement has been made on getting the project off the ground. And with Bluth now in his mid-80’s, it’s becoming more unlikely that we’ll see him get a chance to direct one last film. But, he still remains a beloved figure in the world of animation. He’s even reconciled with Disney, and has been a welcomed guest back on the lot, with many current talent there crediting him as an inspiration. Indeed, without his push for more challenging animation in the early part of his career, who knows where animation today would be. The Disney Renaissance certainly would not have happened they way it did had he not shaken up the establishment in the first place. That in itself makes him an essential figure in the history of the animated medium, and at the same time he has been an imaginative voice that created some truly beloved classics in the process. His journey has been it’s own American Tale, and like the lovable characters he made popular in his films, he was an underdog worth rooting for.