The Disney Renaissance ushered in a Golden Age for the art of animation. After many decades of being a niche market for little kids, animated movies were suddenly becoming big blockbusters once again; films that all ages were enjoying equally. But it wasn’t just on the big screen that Disney Animation was succeeding. Their TV animation department was also blossoming alongside the Renaissance films of the late 80’s and early 90’s. Disney had developed a number of hugely successful Saturday morning cartoon shows that also became highly influential. They often featured already established Disney characters, such as Chip and Dale’s Rescue Rangers and Tail Spin, which starred Baloo from The Jungle Book (1967). They were also developing hit shows with original characters too, like Darkwing Duck and Gargoyles. One show in particular, the Scrooge McDuck centered Duck Tales became such a huge hit that it even spawned it’s own theatrical film. Duck Tales: Treasure of the Lost Lamp (1990) was certainly more ambitious than the average episode of the show, but it was also limited by a slightly larger than TV sized budget that the studio allocated for it. Needless to say, the Duck Tales movie didn’t light up the box office the same way that the TV series had on the airwaves. But, the attempt to make it work did garner the attention of the new regime that was in charge at Disney during the 1980’s. In particular, Animation head executive Jeffrey Katzenberg believed that the popularity of the shows made for strong contenders of a new plan he had for his animation feature department. As the studio was buzzing with the development of their A-list projects like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Aladdin (1992), Katzenberg was looking for a way to put more films in development that were smaller in scale but still retained that high quality Disney style to them, essentially creating a B-move department. There were plenty of good shows to choose from to jumpstart this new project pipeline at Disney, but which one would be the movie to get the first green light.

The block of Disney cartoon series became so popular that even the programming block it spawned was given it’s own name: The Disney Afternoon. The Disney Afternoon block of shows would switch once a new program was launched each year, keeping the line-up fresh over many years. The first new show to jump into the line-up was very unlike the others. After giving the spotlight to many secondary characters from the Disney stable, or entirely new ones as well, it was decided to give one of the Fab Five Disney characters their own show. And who better to headline a new series than Goofy himself. The character, who first launched in 1932 with the name Dippy Dawg, had been a popular mainstay in Disney’s many theatrical shorts over the years. And Goofy was also a character who could be re-molded for any time period as well, which has helped him to stay relevant all these years while still maintaining his core characteristics. His new show would be called Goof Troop, which followed the everyday adventures of Goofy and his son Max, as well as their neighbors, the Pete family. Goof Troop was very different from all the other Disney Afternoon shows, which were often more action adventure based. Goof Troop by contrast was much more grounded, choosing instead to be a domestic, situational comedy. It was a show about the quirks of suburban life, with Goofy often getting himself and others into some very silly situations. And it was a huge hit for the Disney Afternoon. While people enjoyed all of Goofy’s trademark goofiness, it was also the relatable day to day issues that the characters dealt with that helped to make it a favorite with audiences. And what’s more, it was a premise that could easily translate into a theatrical story as well. And that’s what the newly formed B-team at Disney thought as well. It all depended on if Jeffrey Katzenberg thought the same way they did, so a story team was assembled to pitch the idea of a Goof Troop movie.

Some of the earliest people involved on the project included producer Brian Pimental and story writer Jymn Magon. Magon had worked as a writer for Disney Television for some time, including on Goof Troop, so he was an ideal choice to put together the first draft of what would be the script for the movie. Eventually, the team had the script storyboarded out and was ready to present to Katzenberg. However, it didn’t take very long for Katzenberg to see the problems with the story right away. The initial story was too close the original show, and Katzenberg thought it lacked heart. It was just a 80 minute collection of shenanigans with Goofy, and Jeffrey wanted something deeper that he believed would connect more with an audience. So, despite feeling dejected, the Goofy movie team went back and streamlined their script even more. Eventually, most of the side characters from the animated series would be excised from the story, including Pete’s wife Peg and his daughter Pistol. In the end, much of the Goof Troop elements would be left out and this new movie would become more of it’s own entity, with only the characters of Goofy, Max, Pete and his son P.J. being the connecting threads. And even they would be different to their TV counterparts. The character who went through the most significant change was Max. Max has more or less been around since the 1950’s in Disney cartoons, where he was known as Junior in his earliest appearances. He was renamed Max for the series Goof Troop, was was given a very contemporary, 90’s style personality. But for the movie, he would be changed even further. The movie aged Max up to his teenage year, made him less self confident and more at odds with his father. And it was in exploring this aspect of Max beginning to mature and growing in more contrast with his father that the filmmakers found the heart of the film they were looking for.

What was important in getting this story to work was having a vision that could make the more dramatic themes feel natural, which was not easy for a film that starred a character like Goofy. A rising star in Disney’s animation department, Kevin Lima, was tapped to direct the film. This wouldn’t just be his first time directing a feature; it would be his first time directing anything ever. To make it even more daunting, he would have to supervise production across three different studios in three different continents. The Burbank studio would be the main base of operations, but most of the animation would be done off-site at Disney’s international animation studios in France and Australia. While this would’ve normally been a recipe for disaster for a first time director, Kevin Lima proved that he could indeed pull a project like this together. One thing that helped to make him an ideal choice in guiding this project was the fact that he had a personal connection to the story. As revealed in the recent Disney+ documentary about the making of the film, Lima had an estranged relationship with his own father, who abandoned him and his family when he was still young. Taking on this story about a father and son reconnecting through a road trip experience was therapeutic in a way for him, and it motivated him towards getting that sense of bonding across in the story. He also had the benefit of a team of animators who wanted to show that they were more than just the B-team at Disney. While it didn’t have the same budget as say Aladdin, the Goofy Movie would still have some of the best rising talents at the studio eager to show off what they could do. The French studio in fact had a team of twin artists named Paul and Gaetan Brizzi who would later go on to create some of the studio’s most artistically daring sequences in the years ahead. With a story that had emotional resonance in place and the full blessing of Jeffrey Katzenberg, A Goofy Movie was finally set into motion. But it’s success wasn’t always a guarantee.

Unlike all of the other animated features made by Disney at the time, A Goofy Movie was not a fantasy or a grand adventure. It was a road trip movie. The story involves Goofy wanting to take his son Max on a fishing trip in the hopes that it will mend their strained relationship. Meanwhile, Max has become increasingly resentful of the traits he’s gotten from his father, fearing that he’s going to grow up to be just like him, so he’s been trying to reinvent himself in the pursuit of impressing a girl that he a crush on at school; Roxanne. The majority of the movie has the two of them at odds over how they should deal with their relationship; Max wants to break free and Goofy wants to stay connected. Eventually things come to a head when Max deceives his father, having them steer away from Goofy’s plan to go fishing and instead pointing them in the direction of a concert for Max’s favorite singer that he lied to Roxanne about knowing personally in a desperate ploy to impress her. But, through the friction, Goofy and Max come to a realization that they can’t stop either from being who they are. Goofy realizes that Max has his own path in life to follow, and Max realizes that his father is always there for him and that being his son is not a curse like he believed it was. Kevin Lima pointed out one scene in particular where we see this dynamic really coalesce in the story, and that in what he calls the “Hi Dad” soup sequence. In that scene, where the two are forced to take refuge in their car after an encounter with Bigfoot, they start to break down their defenses and find common ground for the first time. It’s a scene that you rarely see in any animated feature, let alone one from Disney. It’s just a parent and their child reflecting on their relationship and getting to the root of why they’ve grown apart. The fact that they managed to make a scene like this work with a character as inherently cartoonish and silly as Goofy is really a testament to how well the filmmakers handled tone and character in their film. It’s not too serious, or too silly; it’s just like a conversation you would see in real life, and that was kind of revolutionary in animation. There’s no wishing on a star to solve these characters problems; this was as true to life as any Disney Animated movie ever got in terms of their storytelling.

One of the major contributors to making A Goofy Movie work as well as it does was the voice cast assembled. Strangely enough, this is also where things could’ve gone disastrously wrong as well. Jeffrey Katzenberg had seen what putting Robin Williams in the role of the Genie in Aladdin did for that film’s record-breaking box office, and he believed that the best way to sell a animated film was to put a celebrity name behind it; something that he would pursue more when he left to start Dreamworks Animation years later. Kevin Lima revealed in recent years that there was a possibility for a while that Goofy was going to be given a celebrity voice. In particular, he had Steve Martin in mind. This distressed Goofy’s official voice at the time; veteran vocal artist Bill Farmer. Farmer had been voicing Goofy since 1987, including in every episode of Goof Troop. He was hoping to also carry that over into A Goofy Movie, but this plan to change Goofy’s voice left him shocked, making him wonder why someone didn’t want Goofy to sound like Goofy. A test sample was made, with Bill voicing Goofy in his normal voice to show Katzenberg how it would actually sound in practice, and thankfully Jeffrey saw the error in his plan and allowed Bill Farmer to continue playing the character the right way. And Farmer’s performance is really extraordinary in the movie, with him finding nuance in Goofy’s voice that no one had even heard before, allowing him to excel in the film’s more dramatic moments. His performance also works perfectly against the vocal performance of Jason Marsden as Max. Marsden was a budding teen actor at the time and Max would be his second major voice role after Binx the Cat in Disney’s Hocus Pocus (1993). What’s great about his performance is that it feels so natural against the shiny personality of Goofy. He doesn’t take the teenage angst too far, nor does he try too hard to sound like a cartoon character’s son. He plays the part naturally, and it makes Max a fully rounded and relatable person. You really get the sense that you would’ve known someone like Max in school or were him yourself. In addition to the leads, voice acting veterans Jim Cummings and Rob Paulsen carried over their roles as Pete and P.J. from Goof Troop without missing a beat, and were joined by an impressive collection of character actors like Wallace Shawn, Kellie Martin, Jenna von Oy, and an uncredited Pauley Shore in the cast.

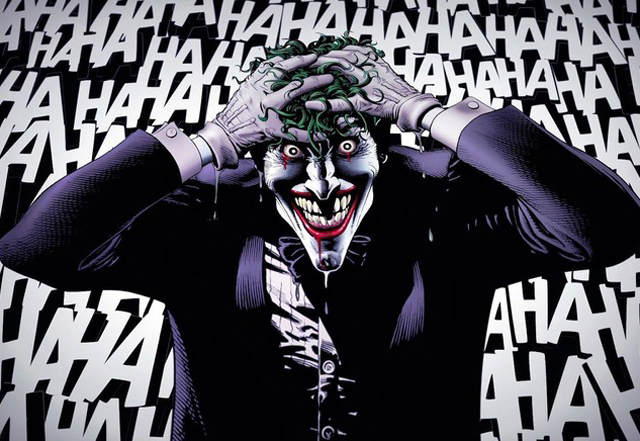

However, there was a speedbump in the film’s road to the big screen. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had been the film’s biggest ally at the studio, abruptly left Disney after a succession dispute with CEO Michael Eisner. Apart from Katzenberg, there was no one else at the Disney Studios that was enthusiastic about having a B-picture production line, so little effort was put into marketing the movie. The film was too far along to cancel, so Disney ended up treating it as an obligation rather than a movie to be treasured as a well as any of their others. The film was quietly dumped into theaters in April of 2025 to little fanfare, and this resulted in low box office results. Critics were also split, because they weren’t sure what to make of it because A Goofy Movie didn’t fit the typical Disney Animation mold. At least their Spring 1995 release helped them to escape the long shadow of the previous year’s hit, The Lion King (1994), which would have buried the film even more. But, even with it’s lackluster launch, this was not the end of the movie’s story, but rather it’s beginning. The movie slowly developed a following during it’s home video release. People gravitated to the more grounded, realistic story at it’s center, especially in the way it tackled the issues of family and fatherhood. The fanbase for this movie grew steadily over the years, and in some surprising demographics as well. One of the biggest areas of support for this film was found in the African-American community. You’ve got to remember that this was long before The Princess and the Frog (2019) and Disney still had not featured any significant character of color in their movies up until the 90’s. Despite all of the characters having a Goofy like appearance, black audiences still saw themselves identified in this film, particularly with the pop singer character in the movie named Powerline, who was primarily based off of singer Bobby Brown, with a little Michael Jackson and Prince thrown in. This was also the first Disney film to ever feature hip hop in it’s soundtrack, which probably also contributed to it’s popularity in the black community. The soundtrack overall is another factor in the movie’s success over the years. It’s a musical, but not in the standard Disney fairy tale style. Each song is unique, mixing rock, country, hip hop, and pop all into one. The finale song, I 2 I, sung by Powerline (who was voiced by recording artist Tevin Campbell) in particular has become one of Disney’s biggest hits over the years, receiving it’s own fair share of remixes and covers in the YouTube era. What is especially great about the re-discovery of this film is that it has shown Disney that not every animated classic needs to be based on a legendary story. Sometimes, a simple father and son road trip is enough to yield a great universal experience for everyone.

Over 30 years the movie has grown in esteem in Disney history; greatly over-coming it’s B-movie status. It’s especially funny seeing how much Disney’s own social media machine is spotlighting this film’s anniversary this year, and not even mentioning once the anniversary of their “A-list” movie from the same year; Pocahontas (1995). It shows that even the B-team could create something that could lay claim to being a masterpiece. And indeed, over time the B-team got to be rewarded for their efforts. Kevin Lima got to move on to directing an “A-List” feature as co-director of Tarzan (1999), and afterwards he even found success as a live action filmmaker, getting the chance to direct the film Enchanted (2007), starring Amy Adams. Though their Paris based studio was closed shortly after the making of A Goofy Movie, the Brizzi Brothers would get to direct some of the most beautiful moments in future Disney features, including the “Hellfire” sequence in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996) and the “Firebird Suite” segment of Fantasia 2000 (2000). Bill Farmer continues to voice Goofy exclusively to this day and has been honored as a Disney Legend for his efforts over his 37 years in the gig. Jason Marsden also continues to voice Max occasionally, and has been an in demand voice actor all of these years as well. One of the pleasing things about this anniversary in particular is that it’s showing just how big this movie has gotten. Disney was especially taken by surprise 10 years ago when they held a 20th anniversary panel at the D23 Expo in 2015. Demand was so high that they had to turn away hundreds of people at the door after the room had reached capacity, and the audience that did make it was electric. After attending last year’s D23, I can tell you that the fanbase has grown even stronger since then. Powerline was an especially popular cos-play at D23, even rivaling people in Jedi or Mickey Mouse dress-ups. It makes sense because all the children who grew up over these 30 years with the movie are now having children of their own, and they are probably re-watching the film with them in a new perspective. Those who originally identified with Max are now finding more in common with Goofy. And one of the greatest legacies that this movie has had is that it’s helped people from multiple generations, fathers and sons, learn to communicate with one another. It’s more than just a goof, it’s a movie that brings people together and that’s why it holds such a special place in Disney history. And that is definitely something worthy to “hyuck” about.