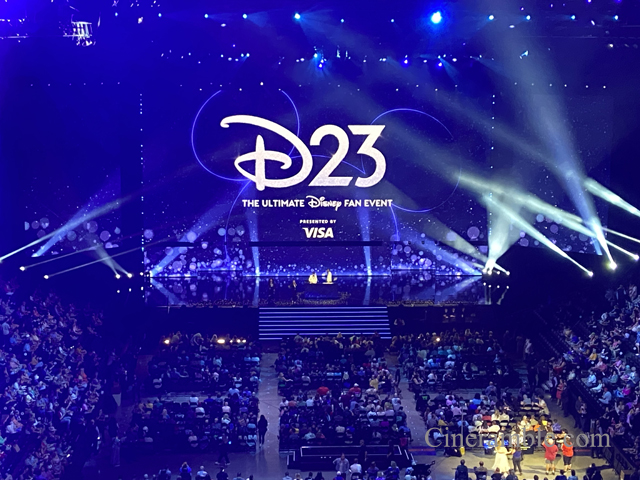

It hasn’t been that long since the Walt Disney Company put on their last Expo in 2022. But in those two short years, a whole lot of things have happened. Mere months after the end of the expo, then CEO Bob Chapek was swiftly removed from his position and replaced by his predecessor Bob Iger. In the aftermath, Iger has been working hard to fix all the problems that manifested during Chapek’s short but tumultuous tenure, and it’s been quit the mess they’ve had to clean up. 2023, which coincided with the company’s 100th anniversary, unfortunately turned into a difficult year for Disney with box office performance taking a big hit after a lot of costly misfires. Through that economic uncertainty, which also resulted in a massive round of layoffs at the studio, Iger faced a lot of pressure to right the ship, which some investors were getting antsy about as the stock price began to tumble. This led to a proxy fight that extended from late 2023 to early 2024, with Iger being threatened with termination by activist investor Nelson Pelz who was trying to buy his way onto Disney’s board. Iger managed to hold off Pelz’s attack and maintain a board of directors that was on his side, but even with that victory, Iger still has a lot of work still to do to get Disney back on track. There are positive signs though, especially at the box office with the massive success of both Inside Out 2 (2024) and Deadpool & Wolverine (2024) this summer. Overall, Disney appears to be using 2024 as a cool down year, allowing them to regroup and reassess their plans by not flooding the market with too many new movies or shows. But, they also need to get people interested in what they have planned for the future, which makes it fortunate that they have their bi-annual D23 Expo event happening this summer. Taking over the Anaheim Convention Center across the street from Disneyland, this is the Walt Disney Company’s biggest celebration, meant to get fans and interested parties alike hyped up about what they have planned for the future, but this year there are definitely changes happening that will make this one unlike any other Expo before.

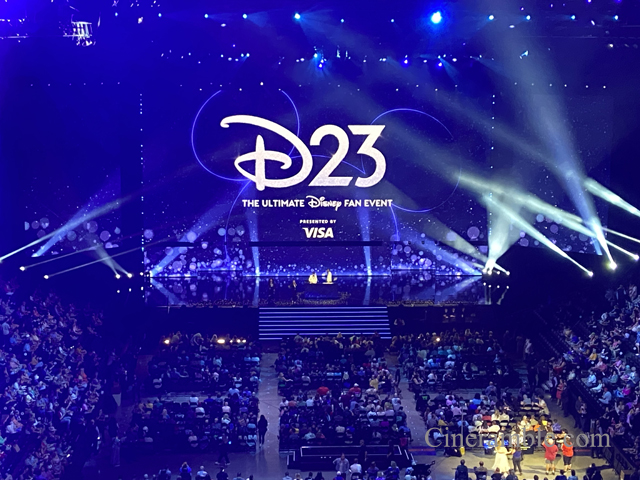

Like all the other past Expos I have covered, I will be taking in all three days on the Expo floor. But due to some ticketing changes, my experience will be significantly different than it has been in past years. Seeing as how they have outgrown the spaces that made available to them at the Anaheim Convention Center, particularly for their main presentations which attract thousands of attendees, Disney has decided to add an even bigger venue to the mix to help give them both more show floor in the convention space but also a bigger home for the big shows. This year marks the debut of D23’s use of the nearby Honda Center as the event space for their biggest shows; namely their Studios Presentation, their Theme Park presentation, and their Disney Legends presentation. The Honda Center, situated about a mile away from the Convention Center, is the regular home of the Anaheim Ducks hockey team and is also used for various other functions like concerts. With a seating capacity of about 15,000 it doubles the seating capacity of what D23 used to seat in their Hall D23 from past years. Unfortunately, hosting in the Honda Center also requires reserved seating, so this made getting a D23 pass a lot more competitive this year. I’ve lucked out in the past managing to get into most shows in Hall D23, but sadly I struck out in getting a ticket to the two shows I wanted to see; the Studios and Theme Parks panels. Thankfully, I did get a 3-Day pass to the convention hall and a Honda Center ticket to the Disney Legends show, but it was not easy. This year was the fastest the D23 has ever sold out, so I consider myself lucky, but sadly my priority picks were gone before I got a chance. But, silver lining, I won’t have to spend most of my day waiting in the queue space to enter the main shows like I have in past years, which will give me a lot more time to take in the Convention floor as well as get an opportunity to see some of the other panels that I otherwise would miss. And I’ll still have that one Honda Center show to close out my experience. So, what follows is my day by day account of the newly re-christened D23: The Ultimate Disney Fan Event 2024, complete with pictures of all the things I see.

FRIDAY AUGUST 9, 2024 (DAY 1)

Going into the first morning of the event, there was very much a notable change in how they were handling the crowds for this year. In past years, queues just to enter the convention center would begin well before the rising of the sun, filling up the sidewalks along Katella Avenue and Harbor Boulevard which border the convention center. This year, there were two big differences that changed this dynamic. One, with the off location venue of the Honda Center taking the big presentations, there was no high demand for a prime spot in standby lines at the Convention Center. Second, with Hall D no longer being the host for the big presentations, the cavernous hall was no open to more show floor, and in addition to that, a new corral for early morning queuing. As a result, there was a far more relaxed atmosphere getting into the venue to start off the convention. The security checkpoints were easy to get through, with no one impatiently trying to rush their way in. There was no running to the corral area; everyone just leisurely walk their way to Hall D and lined up peacefully. This was a very welcome change, and the added bonus was that were weren’t all held downstairs this time in the lower ceiling basement of Hall D. It was an overall less oppressive atmosphere in general, which was a massive improvement over previous years. The only stressful part of the corral area was the impressively long line for the coffee bar. All the corral lines that people queued up in were directed facing a curtain wall, in the center of which was a large arch with a “Welcome” sing above the entry. What shocked me the most was the moment once the floor was open to all of us guests. The curtain was drawn back at the archway, and each line was moved in one by one. And this was done in a surprisingly orderly and quick process. The large mass of thousands of us were on the show floor within less than five minutes. Major kudos to the D23 crowd control team for making this a painless experience, which is very much something we’ve needed for years at this event.

Once through, there were plenty of immediately impressive sights to behold. With the extra show floor this year, there was a clear effort this year to go bigger than ever at D23. All the booths were grander in scale than years past. There was even space open for a whole lot of queue-less attractions. Everyone enters through the newly opened up Hall D, where the seating area for Hall D23 would’ve been in the past. Immediately to the right was the Walt Disney Studio Archives exhibit, which for this year was made into a Car Show. There on the show floor was an open exhibit floor filled with vehicles from across the history of the Disney company. I didn’t have time to stop and look, so I’ll give details later. To the left of the entry was the D23 Member lounge, the Walt Disney Company store and the Spotlight Stage; a barrier less stage area where acts would be rotating continuously throughout the convention. Of course the meatier attractions still laid ahead. Amongst all the show floor booths, many dedicated to partnered retail brands selling exclusive Disney merch, the many different arms of the Disney company also had impressively sized booths that were each must see attractions. One thing that this convention had that made D23 an extra bit of fun was a scavenger hunt challenge called “The Great Pin Pursuit.” One of the most widely collectible things at past D23 events has been enamel pins, so it’s a great idea on Disney’s part to turn it into a game. By doing this, they have incentivized all of us interested guests to explore as many of the booths as we can in order to collect all the required pins for the challenge. The booths which were participating in this were all related to different media wings of Disney; namely Hulu, FX, Freeform, ABC, ABC News, Disney Channel, National Geographic, and of course Disney+, which is where the hunt begins as it’s the place to collect your pin lanyard. A lot of the booths in question showcased a bunch of different hit shows on the different platforms within the Disney Company. The FX booth for instance spotlighted the hit show The Bear with a mock up kitchen made to look like the one in the show. Others had a spot where you could record special videos, like the one with the Disney Channel.

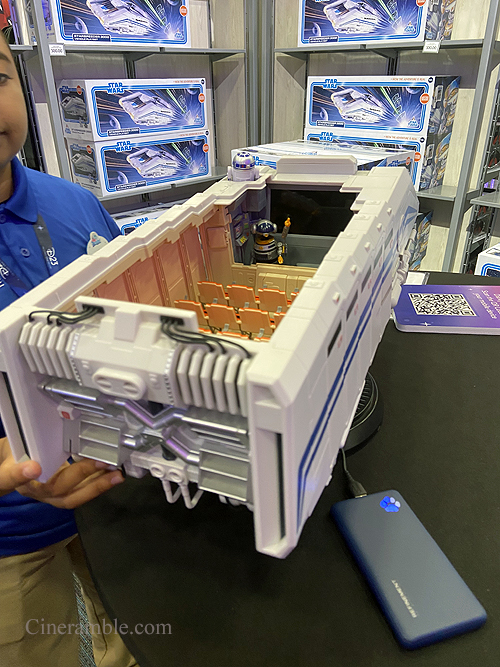

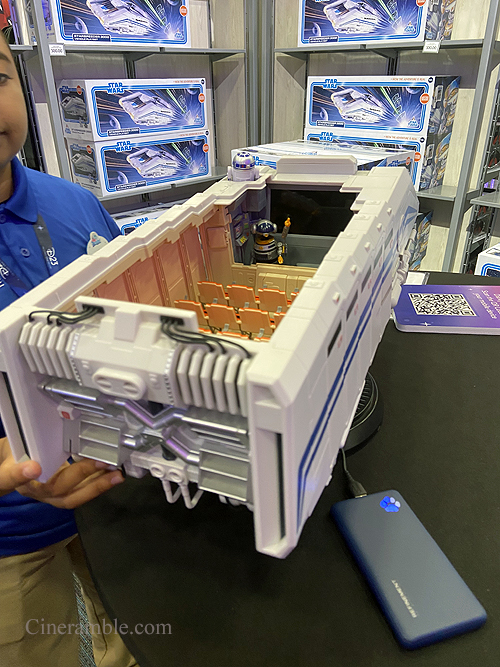

There was a lot of stuff available on the upper levels of the convention space as well. The newer Northern section of the Anaheim Convention Center was where they were housing the Disney Consumer Products booths. This is where Disney, Pixar, Marvel and Star Wars were showing off their new merchandise lines to the public, with each area featuring both sneak previews of merch, some of which was available to buy, as well as additional activities. Star Wars hosted an arcade experience in their booth, while Disney Publishing offered a coffee bar with free tastings of their new Sorcerer Mickey blend by Joffrey’s. But perhaps the best attraction of this section was the area dedicated to Pixar. They built a small miniature golf course themed to the films of Pixar. There were 9 holes in total, with each one dedicated to a different movie. And this wasn’t a cheaply put together course; there was some creative effort put into these different holes. Unfortunately to better give everyone a fair turn, we were only allowed to play 3 holes of the 9. The ones that I played on were themed to Monster’s Inc. (2001), Ratatouille (2007) and Coco (2017). I parred Monster’s, birdied on Ratatouille and bogeyed on Coco in case you were interested. It’s not a huge course, but it was definitely a fun one, and I found that to be one of my favorite floor experiences. The other holes were dedicated to Inside Out (2015), Turning Red (2022), Toy Story (1995) Finding Nemo (2003) and Cars (2006), and for an extra bit of creativity there was a Pizza Planet truck style golf cart out in front. On the same floor, there was another room called the Inside Out HQ. Essentially it was a large activity room themed around the new hit film Inside Out 2 (2024), which included a stand where guests could make their own friendship bracelet, take a picture at a photo op with the characters Joy and Anxiety, and perhaps one of the cleverest ideas of all, take a ride on Mood Swings. Some of these activities had long lines so it’s definitely a time killer with not much else to it. Still, for some casual fun, it’s was a fun little space. Taking up most of the real estate on this floor however was the biggest retail spot of the convention, called the D23 Marketplace. For a lot of the con exclusive stuff, this was the place to go, especially a hot item like the $300 interactive model of the Star Speeder from the Star Tours ride.

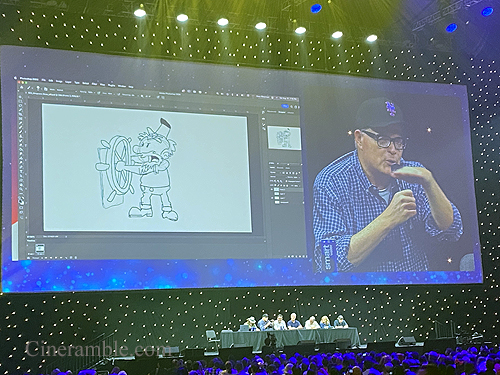

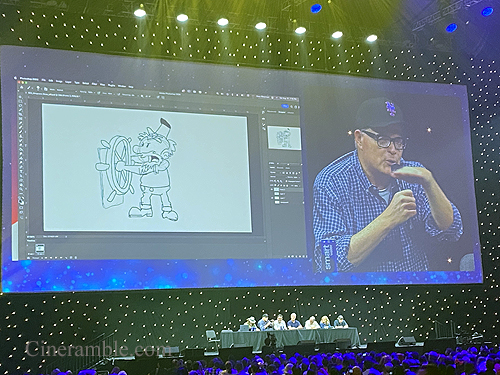

With a lot of my activity dedicated to just looking at the stuff on the convention floor, there was little time to attend the many panels going on at D23. The one that I did manage to take in happened in the late afternoon. It was a panel dedicated to the making of the cult classic A Goofy Movie (1995). Nearly reaching it’s landmark 30th Anniversary, the movie starring the classic Disney goofball is receiving it’s own behind the scenes documentary, which this panel was meant to help promote. The panel was hosted by Disney Legend and producer of films like Beauty and the Beast (1991) and The Lion King (1994) Don Hahn, and the participants at this panel were the new documentaries producers Eric Kimelton and Christopher Ninness. In addition, people involved with the making of the original film were present including director Kevin Lima, story artist Steve Moore, editor Gregory Perler and the voice of Goofy himself, Bill Farmer. The team of panelists all discussed stories about working on the film, but they also talked about what went into the making of the new documentary. Apparently director Kevin Lima had saved tons of behind the scenes footage that he shot himself and it became a valuable source for documenting the story behind the movies making. They showed us various clips from the documentary, and the most surprising thing is that a large chunk of it is animated. What the filmmakers did was use the stories and anecdotes from their interviews with the participants and had a team of animators bring those to life. But not only that, they did it in the style of the movie, with actual hand drawn animation. With that, my interest in the movie skyrocketed and now I am very eager to see the full finished thing. Sadly, we’ll have to wait a while as there is no announced release date yet, but you would imagine that it’ll probably be around the anniversary next year and available on Disney+. It’s especially hilarious how they visualize Jeffrey Katzenberg in the film. It’s a panel that I was very happy to have fit in. I spent the waning hour of the first day walking the show floor. You could sense the smaller crowd as many people were making their way to the Honda Center for the Disney Studios presentation. Sadly, I was not going to be one of them, so I had to get the scoops on the announcements from my follows on social media. Not much was announced that was already known before hand, but from what I heard it was still a very impressive show. For me, it was a low key night getting ready for Day Two.

SATURDAY AUGUST 10, 2024 (DAY 2)

Going into Day Number Two, word got around the floor about all the announcements from the Studios Presentation. Quite a few people I talked to in line were luckier than I and were able to attend the show. I certainly would’ve loved to be in that room too, but a lot of the announcements did make it online immediately after so I was able to be up to date. On this middle day of the convention, my focus was to explore the different experiences that I had yet to do on my first day. I still had a couple stops to go on my Great Pin Pursuit challenge, and these I would say were well worth saving for last as they involved the longest lines. One was a spin the wheel challenge at the Freeform booth, where you would have the chance to win a prize. With it being a Halloween theme game, in promotion of their upcoming 31 Days of Halloween programming block, you either were rewarded a Trick, a Treat, or a special Oogie prize. Naturally, I didn’t win the big prize, but instead ended up with a Trick, which was a plastic spider. Still, I got my pin reward for participating. The bigger activity though was at the ABC booth, promoting the sitcom Abbott Elementary. This booth was a full blown fair set up on the convention floor. Once inside, you had the chance to take part in a few activities, including a hit-the bell game and a stand where you could get your caricature drawn by trained artists. They also offered a complimentary gift of either a tote bag or trucker hat with a patch of your choice. Honestly, you could spend more than hour just in this booth alone, which I kind of did as the line for a caricature was pretty lengthy. But, with this one last booth, I completed my set of pins in the pin pursuit, for a total of 10. It was probably smart to get this activity out of the way early in the convention, as it would free up the rest of my time there for other things. It was also worth it to get my shopping done early. One of the smart things that was introduced at the last Expo and continued here was a virtual queue system for the stores. This helped to eliminate the excessive wait in line it would normally take in favor of select grouping being called throughout the day, similar to what they do at Disneyland for rides.

One other thing they used to manage the lines was a reservation system for the panels. This was introduced back in 2022, and it basically allows attendees to select preferred choices in what panels and experiences they wanted to have a reservation for out of all the available options, and then they would be assigned one randomly from the choices we made. However, unlike last time, all guests were only given one total for the entire convention, as opposed to the one per day we got the last time. This was disappointing, but at the very least the reservation that I did get was for a panel that I did want to see. Even though I missed out on the exclusive sneak peaks at the Disney Studios Presentation, I did get to attend a sneak preview presentation for the slate of upcoming projects from Marvel Animation. Marvel Animation has seen a major surge in popularity recently, especially from the success of the X-Men ’97 series that premiered to acclaim this year. The newest season has just started production so there wasn’t anything new to show us at this panel yet, but the makers of the show did bring out special guests from the cast of the series; Cal Dodd (Wolverine) and Lenore Zann (Rogue), both of whom have been playing these characters since the original 90’s animated series. They shared their favorite moments and lines from the past episodes and where they hope the characters go next in the upcoming season. Next, the creator of the multiversal series, What If?, Bryan Andrews, came on stage to show us a sneak peak of the third and final season coming up soon. In this clips they showed, we could see some interesting new concepts that looked exciting, including a Marvel western and an episode where the Avengers fight in giant mech robots like something out of Power Rangers or Pacific Rim. The next show we were presented with is a series set in the Black Panther corner of the Marvel Universe called Eyes of Wakanda, and it’s an interesting looking exploration of the history of the fictional African kingdom, showing us the origins of the Black Panther title. Next was a Spider-Man series call Your Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man. The art style in this one was interesting, because it felt like a cross between the Spider-Verse animation technique, but applied to the classic Steve Ditko look of Spider-Man comics. The other big scoop we got was that Norman Osborne in this series was going to be voiced by recent Oscar nominee Colman Domingo, who was there on stage to greet us. Latly, we got our first glimpse of the event series Marvel Zombies, which is a spin-off of the What If? Season One episode based on the popular comic series. It also was confirmed to be Marvel’s first TV-MA rated show. The scene we were shown focused on Shang-Chi and his friend Katy (Simu Liu and Awkwafina both returning to voice their character) fighting off against the titular zombies. Overall, an exciting panel to watch.

With half of my second day over, it was time to finally get in an experience at one of the largest and most elaborate booths on the show floor; the one belonging to Marvel Studios. It was clear what the theme for this massive experience was going to be from the outside. The outside wall made the booth look like the office of the Time Variance Authority, or TVA, which has been featured prominently in both seasons of the Loki series on Disney+, as well as recently in Deadpool & Wolverine. The queue switchbacks passed what looks like the reception desk, and once at the front of the line the next stop was a holding room guarded by a uniformed TVA agent called a Minute Man. The guard corralled a few of us into the next room where we would get our pre-show orientation. There was a glass window in from of us looking into another office, and through the glass, we get an appearance from the character Ms. Minutes who appeared in the Loki series (played by voice actress Tara Strong). After she gives us the opening spiel, the door to our right opens up and we proceeded into a set of hallways, each with “time doors” that we could peer into. The various doors had costumes from various Marvel movies, recreating different milestones in the MCU. One was the Mach One suit from Iron Man (2008). Another was Captain America’s, Thor’s and Doctor Strange’s costumes from Avengers: Endgame (2019). Another was T’Challa and Shuri’s costumes from Black Panther (2018). And the last display was of Deadpool & Wolverine, with the costumes of the titular duo. Around the corner there was another doorway where Rocket Racoon was interacting with people who were walking by. Using a new live performance animation technology, the Rocket on the screen disguised as a doorway could capture a hidden actors’ movements and speech i n real time, giving us a very impressive looking and personal one on one experience in this part of the attraction. We were then allowed to move further through an actual open “time door” into another section of the experience dedicated to promoting the upcoming Disney+ series Agatha All Along, with a nice spooky atmosphere meant to emulate the Witch’s Road that will play a key role in the show. After that, we exit while collecting a souvenir pin at end. It was one of the most impressive experiences I’ve ever seen put together for the show floor at D23, feeling almost like an actual attraction you would experience in the theme parks themselves. The level of detail put into this was really impressive, and it actually for a moment made you forget that you were still in the convention center. Maybe it’s a possible preview for what Marvel has planned for the future in the theme parks.

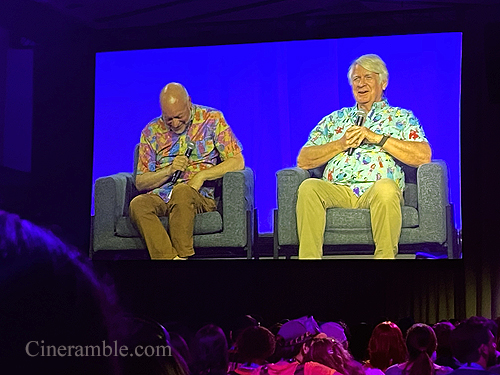

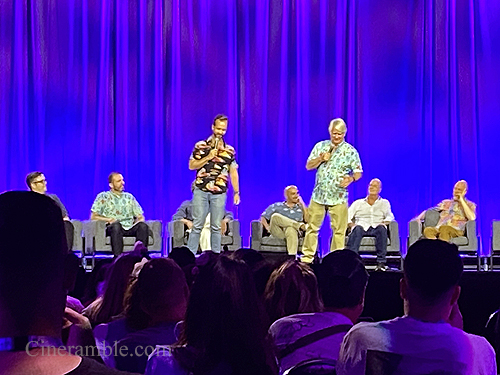

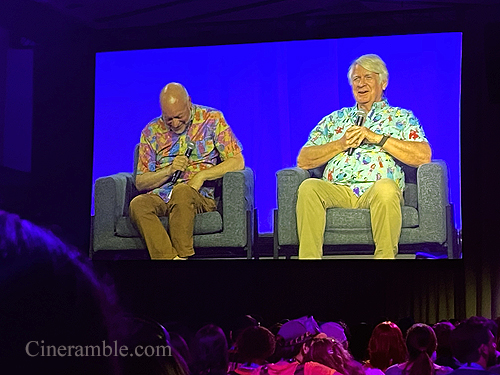

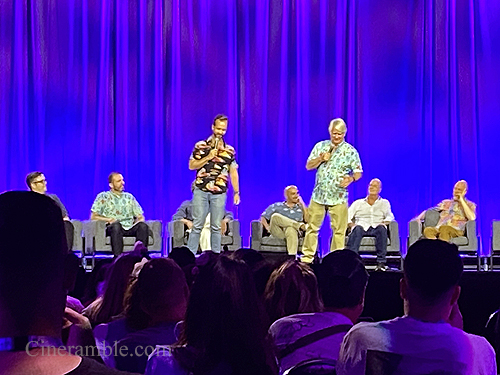

One of the benefits of being in the convention center while many people were leaving to make their way to the Honda Center experience is that you do get to see the show floor cool down a bit, with the lines starting to lighten closer to closing time. As the day was winding down. I was able to get into one more panel in the Premiere Stage housed in the Anaheim Convention Center’s arena building; the same one that I saw the Marvel Animation presentation in. Thankfully, the demand for seating wasn’t as high this close to the end of the day, so I was able to find a seat without much trouble. The final panel for this second day in the Premiere Stage was a show dedicated to the Animation Domination line-up of prime time cartoon shows airing on Fox and streaming on Hulu. The panel opened up with a round-table discussion with the four creators of the biggest shows in the line-up; Seth McFarlane of Family Guy and American Dad, Matt Groening of The Simpsons and Futurama, Mike Judge of King of the Hill, and Loren Bouchard of Bob’s Burgers. The discussion was funny to listen to, given the participants involved and the fact that comedian Jason Mantzoukas was moderating. It was also funny to hear these guys drop a couple of F-bombs during the discussion given that this is a panel at a Disney convention. The discussion went on for half an hour before the next part of the presentation began with three more 30 minute segments devoted to each show. First up, Loren Bouchard returned to talk more about the next season of Bob’s Burgers, with cast and crew from the show joining him. Then Matt Groening and his Futurama team came next, which included voice actors John DiMaggio, Phil Lamar and Maurice LaMarche. Finally, the last half hour was devoted to The Simpsons, with Groening joined by long time producers Al Jean and Matt Selman, director David Silverman, and the voice of Bart Simpson, Nancy Cartwright. Each of the different presentations included Q and A’s with people in the audience as well as sneak peak showings of clips from the upcoming season. The especially exciting news was that The Simpsons was going to be making, for the first time, streaming exclusive full episodes just for Disney+. The animatic we were shown appears to be a parody of National Geographic documentaries, with the Simpsons characters portrayed as creatures from the animal kingdom. It was an eventful and entertaining way to end Day Two, which sadly also meant that this was all going to be over soon.

SUNDAY AUGUST 11, 2024 (DAY 3)

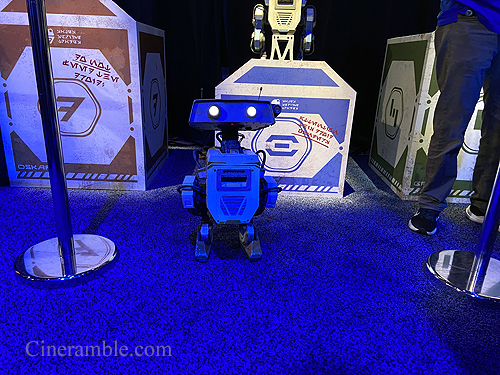

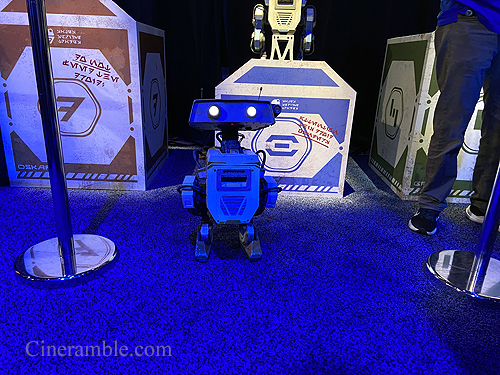

The final day of D23, and you could feel the exhaustion in the air. It was sad that so few minutes were left, but this was still going to be an exciting day, because I would finally get my chance to see the Honda Center set up they had with the closing Disney Legend ceremony. Today I intended to finish all the experiences that I had yet to do up until then. In particular, I had my sights set on the immersive National Geographic experience and the Lucasfilm booth, which put on display a real mock up of their breakthrough LED background tool called The Volume, which they have used on shows like The Mandalorian. First up was National Geographic. The massive booth they had built on the show floor was made for a film presentation experience called the Hexadome Experience. Once inside, a group of guests are meant to stand in the center of the space with a ring of six large screens surrounding them. When the presentation starts, all the screens have images projected on them from various different nature documentaries from the National Geographic library, including the Oscar winning Free Solo and the nominated film Fire of Love. The experience was especially immersive, enhanced with a great surround sound element as well. It reminded me a lot of the Circlevision attraction that used to be at Disneyland. I hope this booth was done as a test for a possible return of the experience to the parks, because National Geographic would be a very valuable partner in that. This was easily one of my highlights of the D23 experience and I was very happy to have not missed out on it. Equally as impressive was the Lucasfilm experience. Not only did we get a chance to see the groundbreaking technology behind the Volume that Industrial Light and Magic have invented to help make immersive background effects feel more lifelike, but guests visiting the booth were given the chance to have a special video made just for them filmed in front of the Volume. Of course I took the opportunity, and I was impressed that they were doing this for D23 attendees in front of a working Volume, but with a real Digital Red camera, the same high quality camera used on the show, operated on a crane by one of ILM’s actual cameramen. I got my short video shot, with a Star Wars droid by my side, and the results were pretty spectacular. Of all the experiences of this D23, these were the absolute not to miss ones, and I’m glad I did not miss out.

One of the most interesting things about this D23 is the fact that it has attractions completely without a queue. Most of the time, the lines will die down by the last day, but this year we had two main booths that people could come and go at their own leisure. One of those was the Disney Studios Archives exhibit, which this year was presented as a Car Show. in past years, the Archives exhibits would be these elaborate mini museums on the show floor which required lines to manage the capacity within it’s walls. This year, no such walls were needed. The cars involved in this showcase were parked out on the floor with no barriers around and you could walk among them and get up and close anytime you wanted over the course of the weekend. Some of the cars on display were obvious choices; there were a couple of Herbie the Love Bugs there, as well as Cruella De Vil’s luxury cars, both from the Glenn Close version and the Emma Stone version of the character. A lightcycle from Tron Legacy (2010) was also on display and a few vehicles used in Muppet movies, which included the open undercarriages that allowed the puppeteers to hide under the seats. One of the other impressive inclusions was a Disneyland parking lot tram that was used back in the 80’s and 90’s, before the construction of Disney’s California Adventure took away the parking lot in front of the park. For theme park fans, this was definitely an artifact that I don’t think many would ever see again. The show floor’s other major exhibit without a line was the Imagineering Pavilion. Here, the Walt Disney Imagineering employees were showing off all the new tech that they had developed for the theme park experiences. Some of the neatest sights here were working Audio-Animatronic models, including a very life like one of Elsa from Frozen (2013). There was also so really neat bipedal droid robots just walking around the exhibit, showing just how advanced interactive robots have gotten. There’s also this neat new invention called the HoloTile floor, which was a type of tile that allowed movement without causing the thing on top to move out of place; something that could be revolutionary for VR experiences. Like I said, this was an open ended exhibit, that is until the last day. Because of the announcements made at the Parks Presentation the night before, a whole new room was opened up on Sunday, with new scale models of the announced attractions available for viewing, and of course the lines were long for this. Sadly. I didn’t get word of this until after the line was cut off, but I did get a side view of the impressive new Encanto (2021) themed ride coming soon to Animal Kingdom in Florida.

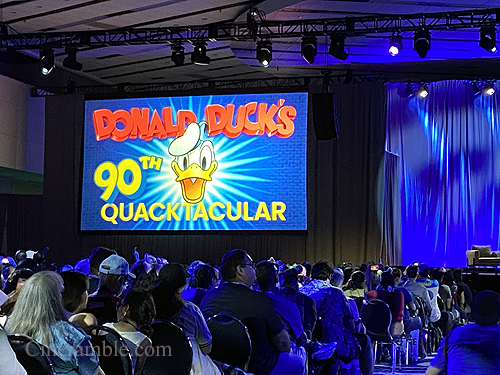

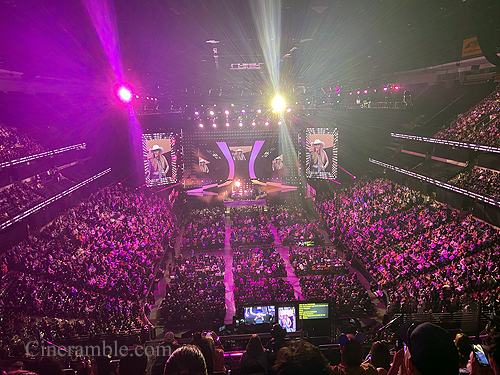

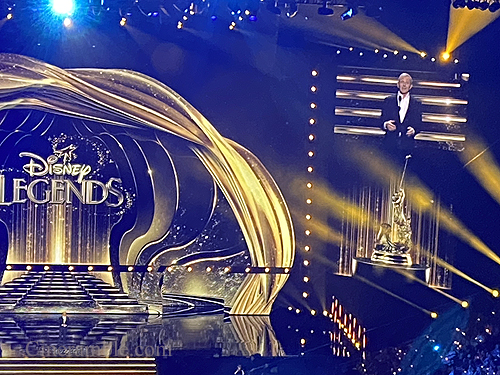

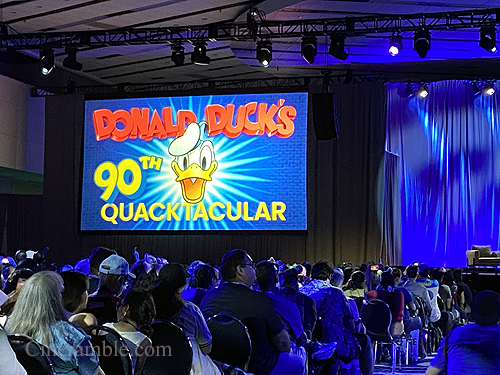

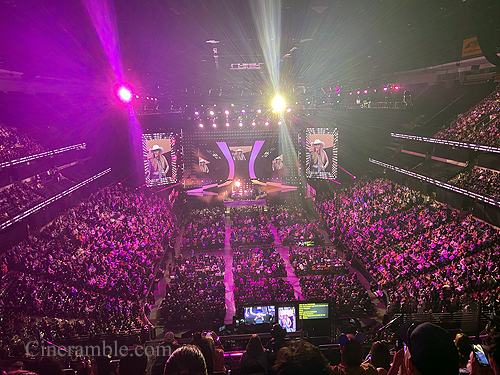

Before I said goodbye to the Convention floor to make my way to the Honda Center for the closing night show, I did manage to fit in one more panel before hand. It was a panel discussion celebrating the 90th anniversary of Donald Duck. The panel was presented to guests in multiple parts. Two people from the Disney Archives showed the audience a slide show of rare artwork from their vaults showcasing the history of Donald Duck, from his debut in the short The Wise Little Hen (1934) to the present day. The second guest was a film preservationist who discussed his work at the Disney studio with restoring the old classic cartoons, and as a special treat we were given the premiere of the newest restoration of a Donald Duck short from the 1940’s called Donald’s Off Day (1944). Finally there was an interview with two current Disney artists who have worked on Donald Duck recently; animator Mark Henn, who directed the short D.I.Y. Duck (2024) for Disney+, and the longtime voice of Donald, Tony Anselmo. Anselmo shared some interesting stories about being trained by Donald’s original voice actor Clearance Nash, and how he approaches voicing Donald today and how it’s changed over the 40 years he’s been doing it. At the end of the panel, the special guests and all of the audience sang a “Happy Birthday” song for the character, with Anselmo even singing in character, and of course a theme park Donald character ran on stage to take in that celebration. A fun little panel that offered a great overview of the incredible 90 years of the character. From there, I spent what little time I had left on the show floor to take in the who atmosphere and see if I missed everything. In D23’s of the past, I usually would like to linger and catch the winding down of the convention, but this year would be different. I had to get over to the Honda Center for my Disney Legends show, so sadly I had to leave the show floor four hours before it would actually close. The Honda Center takes some time to travel to, so I needed those extra hours. Thankfully, Disney was providing complimentary shuttles for all the guest who were attending the night time shows. I got there about half an hour before showtime, and thankfully getting through security was a breeze, helped by the venue’s “no-bag” policy. I took my seat in the massive venue, an I can definitely say just from that first impression this was a major upgrade from Hall D23.

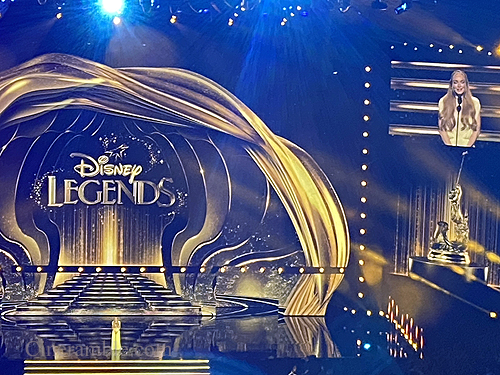

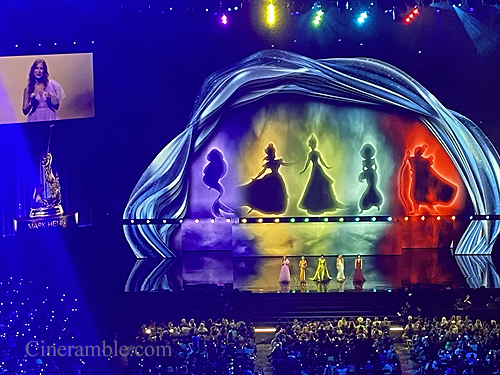

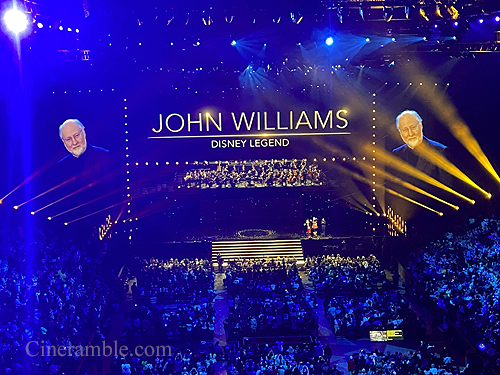

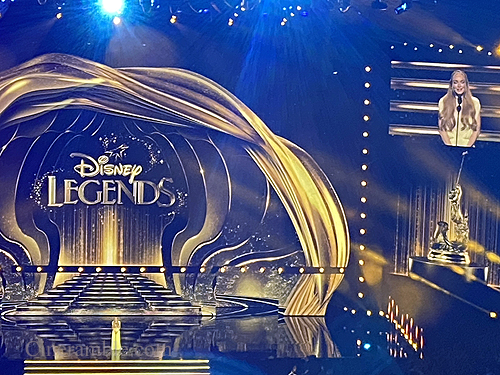

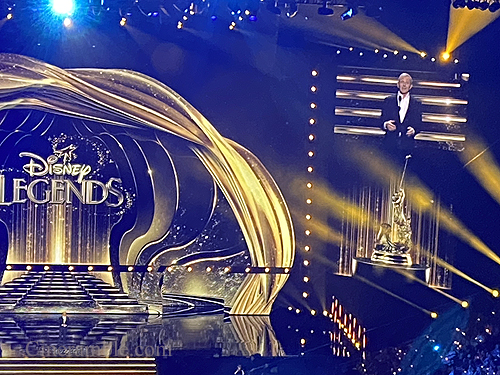

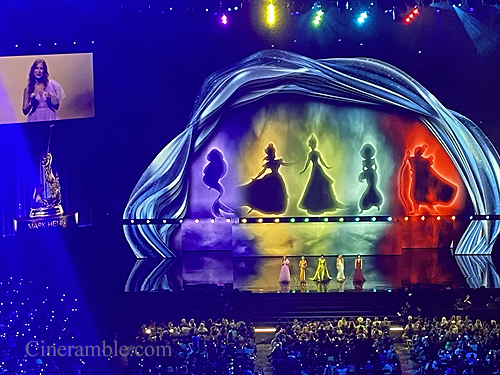

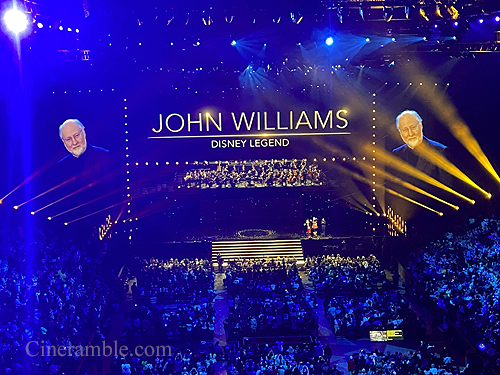

Now began the finale to my three days of D23 and it was a far more elaborate show than I anticipated. These ceremonies had always been special events in the past, but that was in the context of being part of a convention experience. This time, Disney put some production behind this show, making it like it was a legit awards ceremony like the Grammys or the Oscars. We got special guest appearances and live entertainment put on a really impressive show. And it kind of makes sense that Disney wanted to make a bigger deal out of this, because this is the first Legends ceremony that was going to air for the public view via Disney+. The honorees span across the Walt Disney Company’s history and represent it’s many different departments too. The honorees this year were Harrison Ford, Jamie Lee Curtis, Angela Bassett, Martha Blanding, Colleen Atwood, James L. Brooks, James Cameron, Miley Cyrus, Steve Ditko, Mark Henn, Frank Oz, Kelly Ripa, Joe Rohde, and John Williams. Each presentation of the award gave each honoree a big moment that included some neat surprises. The highlights I would say were Jamie Lee Curtis leading a sing along with the audience of the Sherman Brothers’ “There’s a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow;” Martha Blanding, a theme park veteran who broke down so many barriers as a Black American employee who rose up the ranks of the Disney company; and Mark Henn, the animator of so many famous Disney Princesses, being honored by the voice actresses of his characters, those being Jodi Benson (Ariel), Paige O’Hara (Belle), Linda Larkin (Jasmine), Ming-na Wen (Mulan) and Anika Noni Rose (Tiana). There were many special surprise guests as well, like Jodie Foster, Lindsey Lohan, Zoe Saldana, and even Danny DeVito. But, the closing of the night was especially incredible as we got a live orchestra to perform the music of on of the honorees, the legendary John Williams, who sadly was unable to be there in person. Naturally the medley of music was from the Star Wars and Indiana Jones films and I definitely have to say that the orchestra was spot on. The show ended after with a group photo of all the honorees and a blast of golden confetti from the rafters. And that’s how my D23 experience came to an end, with a big finale.

This D23 generally had a much better vibe to it than the last one in 2022. The previous D23 came at a time of uncertainty for Disney as it was at the peak of dissatisfaction with the Chapek regime at the company. The most notorious story to come out of D23 2022 was that Chapek was booed during his brief appearance at the Legends ceremony of that year. It was very different this year, as I could very much hear a huge roar of cheering from the crowd when Bob Iger walked on stage. All of the announcements at this convention seemed to get the warm reception that Disney was hoping for. From what I heard from a lot of people they were especially excited about the upcoming stuff they saw at the Parks Presentation. I feel bad about missing out on the big shows, but I’m happy I did get to have one experience inside the Honda Center. The new venue is definitely a better place to be holding these presentations and I hope they continue using it in future D23’s. In general, there seemed to be a much bigger effort to impress this year than in past D23’s. The more room on the show floor gave us bigger experiences to enjoy. I was especially impressed with the Marvel and National Geographic experiences, which felt like full blown attractions worthy of the theme parks; which makes me think Disney was using them as test runs for feedback in their future plans. I also love the introduction of the Pin Pursuit game, which gave guests an extra incentive to try out more of the experiences on the floor. Even the third party booths were more elaborate than usual. I just hope that in the future they can make the ticketing easier for their biggest shows. Or maybe I was just unlucky and had to settle with what I got, which is still more than most. Thankfully, I was still able to spend all three days there and have fun time. The best thing was that I had more time in general to do as much as I could, because I wasn’t spending half of my day waiting in line for the big shows. And at least I knew going in I wasn’t going to see two of them, so I didn’t have the disappointed feeling like the last D23 where I barely missed the cut off. Overall, I am psyched about the future of the D23 experience and my hope is that the next on in 2026 will be just as grand if not better. Thank you once again Disney, and in the words of the late great Richard Sherman, “Have a Great Big Beautiful Tomorrow.”