Today is Earth Day and for many of us it’s a day where we take time to actively do our part to help keep the environment clean and healthy in some way. But, at the same time, it’s also a time where we worry greatly that not enough is being done to keep the water and air clean and the resources that we live on sustainable. For many, getting the message out that the Earth needs saving is a chore in of itself. At a time when a few people out there are less willing to accept scientific consensus about the state of our world today, we are finding ourselves in a perilous situation where ignorance is the biggest threat to our world. But, how do you convince people of the facts when the science may sometimes be too complex to understand or the message too dire? That’s when you call upon entertainment to help out. Environmental issues have long been an important subject in the mediums of art, song, and film, and sometimes they have effectively managed to move and motivate people to want to take action and do what’s best for the planet. The only problem is, when relying on forms of entertainment to get the message across, environmental movements can sometimes run the risk of minimizing their cause by turning it into a cultural fad rather than a lasting legacy. Entertainment politics have just as much of a sway on the effectiveness of an environmentally conscious program as it would on any other subject, and it wouldn’t be all that crucial if the message weren’t so important. When it comes to environmental issues as entertainment, we unfortunately have a very inconsistent legacy that sadly undermines the message in a way that in some cases does more harm to the world than good.

Not that it’s a bad thing that Hollywood tries at all to make environmentally conscious films. Not trying at all to address environmental issues would be even worse. What specifically is the problem with some of these so-called “green” films is that they have to adhere to commercial appeal in order to be made in the first place (especially if they are backed by a studio) and in the process, they unfortunately find themselves compromised. This can happen in a variety of ways. Either the message of the film becomes diluted down so much to childish simplicity that it no longer has any weight at all, or it is exploited in an effort to satisfy the studio or filmmakers’ own agenda. As a result, few if any quality films are made that take environmental issues as seriously as they should. There are many degrees in which a lot of environmental films fall short, but I think the greatest problem overall is that too few of them actually hold their audience to task for the problems they are addressing. I know that few people want to go to the movies to be lectured to, and it’s often a sure fire way to turn your audience off to a film, but what a lot of filmmakers who take environmental issues seriously need to know is that their audience needs to feel the importance of the issue; not just have it presented as a story point. An audience needs to relate to an issue just as much as it needs to relate to the characters. It has to hit them personally, and make them see that the problem won’t be solved until they make the move to change it themselves. Now, one person motivated like this may not be the agent of change, but a whole bunch of people can and that’s why it’s crucial to get the message right in a film. And even more importantly, it’s crucial to recognize where the message is effectively getting through and where it is not.

Environmental issues on the big screen has been a long evolving thing, changing very quickly over time to observe the changing attitudes in society as a whole. Social films have always been a part of Hollywood, but they were more centered on human conflicts and despair rather than dangers facing the world itself. You can see this in films like The Grapes of Wrath (1940), which brilliantly documents the hardships facing a family of migrant workers heading to California after being displaced by the Dust Bowl of the Midwest in the 1930’s, without ever discussing the environmental factors that led to the famine in the first place. Postwar Hollywood took on environmental issues more definitively in the 50’s, but it was from a place of Cold War paranoia, where nuclear annihilation was seen as the biggest threat to the environment. Even still, environmental consciousness became more important in these years, and likewise, Hollywood found stories worth telling that could motivate millions of viewers to take action. You can see this in allegorical sci-fi films like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), where an alien visitor warns the people of Earth to take better care of their world, or else face annihilation themselves. It was pointed, but in a way that made audience take note that keeping the world a clean an orderly place was the best way to make their progress society as a whole. You can also see this reflected in a slew of PSA films that were produced around this period, which among other things taught people how to keep their homes sanitary, how best to dispose of hazardous material in a safe way, and also how to avoid environmental hazards in their own backyards. Some of these were pretty naive and sometimes completely absurd (“duck and cover” as a response to a nuclear blast for instance), but, Hollywood was finding out with these movies that taking on such issues in their movies could indeed affect social action.

It wasn’t until the 1970’s when Hollywood’s message machine and the call for action on environmental issues finally coalesced into one. It was an era when it came abundantly clear that the Earth’s environment was in danger and that action needed to be taken. Even President Richard Nixon, of all people, saw the importance of doing something to save the environment, which led to the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Likewise, Hollywood made an effort to state that environmental issues were no longer just a minor thing, but instead the most important thing and that we as a species could no longer just ignore it. In this time, you saw a lot of movies that discussed the effect of pollution in our air and water, the clear-cutting of forests, and the negligence of industry that allowed for environmental degradation to happen. What is special about the movies from this era is that they weren’t afraid to be bleak, which surprisingly proved to be a more effective tool in getting the message across. With Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), you had a noir thriller centered around a real case of corruption in Depression era Los Angeles, which showed how manipulation of resources could degrade a once vibrant landscape and destroy the livelihood of those who worked the land. The China Syndrome (1979) showed how corporate negligence at a nuclear power plant could lead to a possible destruction of a city within the blink of an eye, and show that maybe nuclear power wasn’t the best option for our energy production. And there was also Soylent Green (1973), a disturbing dystopian look into a future plagued by overpopulation and food shortages compounded by pollution. It’s a film where even the solutions to the problem are the stuff of nightmares. But, what each of these films managed to do was to wake up the population to issues about the environment that were starting to affect us. For a while, people did make an effort to consume less, hold corporations accountable, and do their best to improve the environment. But as society changes, the message also changes, and newer messengers don’t quite have the same urgency to get the message out as before.

Since the 70’s, new facts have about the environment have made the issues more complex and as a result, far more harder to stress to a larger audience. As a result, a new trend of environmental films have arisen that unfortunately dumb down the issue in order to make it more appealing to a general audience. In some cases, filmmakers come across looking like they don’t care about the issues they are addressing and just want to make it appear like they do care just so that they can win some credibility points from environmental groups. Unfortunately, if the whole project becomes disingenuous, it trivializes the message as a whole. Case in point, the films of Roland Emmerich. Emmerich is a filmmaker notorious for making shallow statements in his films on a variety of subjects, but none more so than with his environmental films The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and 2012 (2009). The reason his films come across as shallow is because it’s clear that he’s ignoring scientific reality in favor of creating his own outlandish scenarios in order to add extra spectacle to his films. That’s how you end up with preposterous segments in his movies like John Cusack outrunning a supervolcano explosion in a Winnebago from 2012, or Jake Gyllenhaal literally being chased down a hallway by the effects of global warming in The Day After Tomorrow. I don’t think that Roland Emmerich isn’t concerned about the environment, but his shortcomings as a filmmaker only makes the message in his movies seem ridiculous and as a result, easier to dismiss; and that in of itself is a big disservice to environmental causes. If you want to help the environment, you need to deal with it honestly, and not trivialize it with your own indulgences. It’s sadly something that far too many filmmakers do nowadays with environmental movies. Spectacle only makes the issue seem smaller, because you are associating real environmental problems with Hollywood magic, and reality has no magical solution.

An even worse problem with environmental movies today is how they are sometimes exploited for the purpose of a different agenda. In particular, one thing that I have noticed with some environmental movies is that they scapegoat all environmental problems on some corporate entity. Sure, many corporations over the years have been contributors to environmental degradation, but taking an anti-corporate stance in your movie is no solution to the problem of fixing the environment. As a result, you have a movie that is undermined by it’s own lack of urgency and it’s insistence of shifting the blame to someone else. By doing so, you creating a sense in the audience that they themselves no longer have a responsibility to the environment, because they only see the evil corporation as the offenders and not themselves. For an environmental message to work, it must put the responsibility on the viewers shoulder to do something about the issue, and not let them off the hook. That’s why conventional black and white morality in environmental movies makes the message far less effective. You can see this in James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), where he trivialized environmental issues by creating this corrupt straw-man corporate entity as an obvious antagonist within his story. Had he presented a more even handed portrayal of the corporate characters, showing the complexity of their dilemma as well, then you might have had a more reasoned examination of the issue, with the environmentally conscious side standing up to scrutiny. Instead, it just appeared that James Cameron wasn’t interested in a two sided argument, and that he wanted his beliefs presented without impediment. Sure, he still managed to deliver a billion dollar hit movie, but it’s not the environmental arguments that we remember, and it led to a less motivated audience because they were never able to connect with the issue.

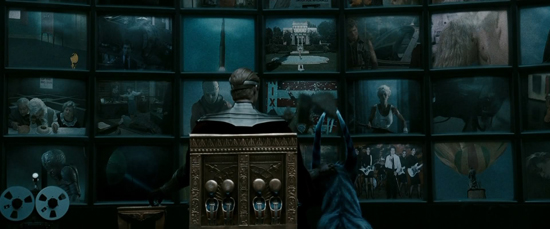

There are many right and wrong ways to deliver an effective environmental story, and sometimes the best way to do it is to not appear on the surface like you are an environmental film at all. That’s what made the films of the 70’s like Chinatown and Soylent Green so effective because they were compelling stories on their own that just so happened to involve environmentally relevant issues. What I think to be one of the greatest environmentally conscious movies of all time does this perfectly; the Pixar-created animated film Wall-E (2008). Wall-E is primarily just a love story between two robots, but as the story goes along, you see that it has a profound statement to make about man’s responsibility to his environment. In the film, Wall-E the robot travels to the far reaches of space, and finds the remnants of humanity living on a space cruise ship, confined to lounge chairs and absorbed into distracting social media. And all the while, their home planet is a garbage filled wasteland, which Wall-E has alone been tidying up. If that’s not a compelling statement on our societal problems contributing to environmental degradation, than I don’t know what is. And the movie has the intelligence to not let the viewer off the hook and asks us what is in our best interest going forward with environmental issues. Contrast this with Illumination Entertainment’s adaptation of The Lorax (2012), which took every bad environmental movie cliche, and distracted it’s audience with trivial nonsense while at the same time pretending like it cared. Dr. Seuss’ original story was about the dangers of over-consumption and it taught it’s audience to be more responsible with a compelling one word warning: “Unless.” The CGI animated Lorax instead proved to be the most hypocritical of films by minimizing Seuss’ message and shamelessly cross-promoting itself with corporate sponsors, effectively promoting more consumption, which is an insult to Seuss’ intent. This shows that a movie that sells itself as environmentally conscious may in fact not be, and that the more unexpected the environmental message the better it will affect it’s audience.

Overall, environmental movies should not be taken as just light entertainment, because the real problems we face are far too important to ignore. For the most part, it’s a problem that is more closely associated with fictional environmental films than say something made in the non-fiction medium like a documentary. But, even in the documentary field, it’s important to have a clear message that connects with the audience and makes them want to take action. For Hollywood films, it matters to make environmental issues relatable, and that means not being afraid to take a few risks no and then. I’m sure viewers became more concerned about the preservation of wildlife after they saw the death of Bambi’s mother from a hunters gunshot. And I’m sure that Soylent Green made more people aware of their daily consumption, and that it was perhaps better to hold back a little, or else far worse things could happen. Essentially, good stories told well can deliver a strong message on environmental issues, but the real change comes from not holding back and putting a sense of urgency into the minds of the audience. When you trivialize the issue by mixing it too much with Hollywood style entertainment, then you create a passive indifference in the mind of the audience, leading them to take the issues facing the environment less seriously. We’ve seen before that it can be done, but it must respect the intelligence level of it’s audience. An audience will want to make a difference only if they’ve been moved and inspired. And you can find far little inspiration in a movie that treats global catastrophes as spectacle, or presents a scapegoat that let’s the audience off the hook. And you’ll find no more insulting environmental message than the Lorax hocking “green-approved” cars and IHOP pancakes. Seriously, shame on that movie. With our world growing increasingly fragile, it’s more important that we make environmental films that get real results and motivates more people to do the right thing. It’ll be good when the fact that they are entertaining as well can be the only real by product in the end.