With a week to go before the Summer movie season gets underway, it makes sense to look over the year so far to see what the upcoming months will have to follow up on. This year’s Winter and Spring movie seasons have been remarkably strong, both critically and financially. Usually associated as being Hollywood’s dumping ground, we saw the early months of 2017 marked with some surprising quality efforts from unlikely places. We got a shocking twist upfront when M. Night Shaymalan finally made a movie that everyone liked with Split. Jordan Peele of Key & Peele fame made a remarkable directorial debut with his controversial thriller Get Out, which earned raves upon release that are usually reserved for Oscar nominated fare. The Lego Batman Movie gave us even more hilarious fun with it’s plastic brick built world. There was also solid thrills in movies like John Wick 2 and Kong: Skull Island and Hugh Jackman’s Wolverine was given an effective sendoff in the acclaimed Logan. Ironically, the movie I liked the least from the first half of this year ended up being the highest grossing overall; the still loathsome Beauty and the Beast remake from Disney, which has grossed over a billion worldwide as of this writing. Overall, it’s a solid start to the year, and one hopes that the upcoming summer season, where Hollywood makes room for their big guns, manages to keep the momentum going. Like years before, I will be looking at the months ahead and tell you which movies are my Must Sees, the movies that have me worried, and the ones that I recommend you skip entirely. Keep in mind, these are just my initial thoughts about the movies based on my expectations and how I respond to their marketing. There could be some surprises and/or disappointments out there, and I admit that I’m not the best handicapper. So, with that, let’s look at the Summer of 2017.

MUST SEES:

GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY VOL. 2 (MAY 5)

Let’s start this look at the summer by spotlighting how it’s going to begin. Again, Marvel Studios is showing that they own this opening spot in the month of May, which has been so lucrative for them before with blockbusters like both Avengers, Iron Man (2008), and Captain America: Civil War (2016). This year, they are launching the Summer with the sequel to one of their absolute best films. Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) was a surprise hit when it debuted, taking a relatively obscure comic and turning it into a phenomenom thanks to a stellar directorial effort from James Gunn and star making performances from it’s cast. The same team returns intact to take on another adventure, and the trailers are promising us more of the same, which is not necessarily a bad thing. Guardians stands out from the rest of the Marvel field and it’s strengths are worth elaborating on in a sequel, including stuff like hilarious banter between the characters, colorful worlds to explore, and a world-class retro soundtrack. I’m especially excited to see the new faces added to the mix, especially the perfectly cast Kurt Russell as the father of Guardian member Peter “Star-Lord” Quill. Making a sequel to such a beloved first outing is going to be difficult no matter what, with everyone’s expectations now up so high. I have faith that James Gunn, Christ Pratt and the rest can pull off something special with this. Even if it’s not as good as the first, most of us will still appreciate it if it at least leaves us entertained. And one thing’s for sure, that Baby Groot is going to be everywhere this Summer, so buy those toys now before they’re gone. Marvel’s win streak should comfortably continue with these Guardians in place.

DUNKIRK (JULY 21)

Christopher Nolan’s name at this point in his career is synonymous with the word “epic.” Every film he makes now is big in scale and scope, and it’s to his credit that he continually focuses his vision onto many varied subjects, giving solid diversity to his body of work. He revolutionized the super hero genre with his Dark Knight trilogy; he explored the cosmos with Interstellar (2014); and he even delved into the endless possibilities within the human mind with Inception (2010). With his newest film, however, he’s doing something very different, and that’s giving us a historical account of a harrowing event from World War II. The Siege of Dunkirk is an interesting subject for Christopher Nolan to take on, though one that you would hardly expect. The real life story is not one that’s about conflict, but instead about survival. Half a million British soldiers were surrounded by German forces, trapped in the titular coastal town with the sea as their only window of escape. Miraculously, most of the soldiers made it to safety in one of the greatest rescue efforts in modern history. The scale of the event is probably what drew Nolan to the project, providing another opportunity for him to work with large format cinematography such as IMAX, which he’s used to great effect before. My hope is that, like most of his other films before, he manages to balance the human emotion amidst all the spectacle. More than anything, I’m just intrigued to see a director of his caliber working within this kind of genre. This is sure to be one of the most epic scale war films ever made, and my hope is that it also stands as one of the best. Anytime Christopher Nolan stands behind the camera, it signifies something eventful; something which few directors can do nowadays.

SPIDER-MAN: HOMECOMING (JULY 7)

I know that a lot of you out there are probably sick of Spider-Man movies by now, especially now that it’s going into it’s second revival after the previous one fell flat. But, the truth is, this may actually be the first “real” Spider-Man movie we’ll have seen on the big screen; not one that’s made by outside studio forces, but a true honest to goodness adaptation of the comics from Marvel themselves. After getting the rights to the character back from Sony in a profit sharing deal, Marvel has quickly worked the webslinger into their Cinematic Universe, and he managed to already delight audiences again with his brief appearance in Captain America: Civil War. Now, with his own film, Marvel is making the smart decision to not go all the way back to the beginning and start with another origin story, instead choosing to create a new story with an already established Spider-Man. Tom Holland returns, and he looks to be just as charismatic here as he was in Civil War. It works to the films benefit that here we’re finally seeing an actual teenage Peter Parker that’s truer to the comics than the late-20’s actors who have stepped into the role before. The inclusion of Robert Downey Jr. as Tony “Iron Man” Stark is also a great inclusion for this film. But, what makes me most excited is the casting of Michael Keaton as the villainous Vulture. What a casting coup for Marvel, managing to to get cinema’s first Batman and having him cross the aisle, away from DC, to play a Spider-Man villain. That alone is worth seeing, and Keaton looks so perfectly menacing in the part. Overall, it should indeed be a very welcome homecoming for Marvel’s friendly neighborhood webslinger.

DETROIT (AUGUST 4)

Director Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal have had a pretty good and lucrative collaboration over the last decade. They both won Oscars for their landmark war drama The Hurt Locker (2009); a historic win in Bigelow’s case. They then followed that up with a comprehensive historical account of the hunt for Osama Bin Laden in Zero Dark Thirty (2012), an acclaimed and cntroversial film in it’s own right. Now, the two have turned their attention to another interesting subject; the 1968 riots that tore apart the city of Detroit during one of the most heated periods of the Civil Rights movement. Bigelow’s intense, documentary like style could be a great fit for this subject, putting us right into the thick of the event, helping us to see what it was like to live through such a moment in time. Not only that, but with the tumultuous time that we are living in now politically, and with tensions between civilians and law enforcement growing even higher, this could be a very timely history lesson as well. My hope is that Bigelow and Boal applies their no-nonsense style of story-telling to this subject and gives us a captivating and intense experience, allowing us to see an unfiltered look at American history. The inclusion of Star Wars‘ John Boyega as a central character also looks promising, as the up-and-coming actor is due for a quality lead role outside of the big franchsie. Historical films usually are a hard sell during the summer; especially ones that take on such a touching subject matter. But, this one looks to be in some capable hands.

BABY DRIVER (JUNE 28)

Another director who manages to garner attention every time he puts a new movie out is Edgar Wright. After a disappointing development cycle on the movie Ant-Man, where he famously parted ways with Marvel over creative differences, Wright returns with a new spin on the heist genre. Instead of relying on his usual collaborators Simon Pegg and Nick Frost to fill out the cast, he’s instead going in a different direction, working with a largely American cast and focusing far more on an action style rather than a comedic one. Sure, it’s still carries some of Wright’s trademark sense of humor, but what this movie is also showcasing is an added sense of creativity in the action set pieces. This is Edgar Wright moving beyond the realm of parody and finding new footing in the high octane action world; an area that he may actually prove to be a natural at. While he is trying new things, my hope is that some of Edgar Wright’s trademark visual flair, which he refined throughout his Cornetto trilogy, manages to translate over, and this stylish trailer has me believing that it did. The supporting cast in this film also looks impressive, with Jamie Foxx and Jon Hamm making an impression as two seasoned criminals, and Kevin Spacey as always commanding the spotlight whenever he’s on screen. Hopefully the fresher faced leads (Ansel Elgort and Lily James) can hold their own against these veterans. At the very least, it will be interesting to see Edgar Wright work out of his element in a promising new field of film-making.

MOVIES THAT HAVE ME WORRIED:

WONDER WOMAN (JUNE 2)

To be honest, I am cautiously optimistic about this one. Sure, DC has been not very effective in launching their ambitious cinematic universe. Batman v. Superman; Dawn of Justice was a convoluted mess, and Suicide Squad, while not a terrible film, did alienate DC even more from comic book fans with it’s messy execution. Now, with Justice League on the horizon, DC desperately needs a solid hit in their stable, hitting the mark with both fans and critics. And believe me, a lot of us want this to go well, because Wonder Woman is a superhero you don’t want to see cinematic-ally ruined. On the plus side, Gal Gadot’s appearance as the titular hero in Batman v. Superman was one of that movie’s more positive aspects, and it did make me interested in seeing a full feature devoted to the character. The trailers so far have done a fine job showing off the spectacle of Wonder Woman’s world, from the sumptuous locals of her island paradise home to the murky war zones of Europe during the Great War. My hope is that the film manages to escape the studio interference that plagued it’s two predecessors and manages to define itself by it’s own merits. This will be the first time that a female superhero has been featured in her own film, something that DC managed to do first before Marvel, so a lot is at stake with how well this feature performs. Again, DC’s track record of late has tampered down many of our expectations, but hopefully this will be the film that finally rights the ship for DC. Otherwise, the Justice League they’ve been so eager to form will be doomed before it even starts.

PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN: DEAD MEN TELL NO TALES (MAY 26)

Fourteen years ago, Disney did the unthinkable and managed to turn a film based on one of their theme park attractions into a box office and critical success. Largely thanks to Johnny Depp’s charismatic performance as Captain Jack Sparrow, we had one of the unlikliest of franchise born. Unfortunately, it’s a franchise that also has lost a lot of it’s luster. The two follow-up sequels (Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End, which were shot simultaneously) did succeed at the box office, but were considered too convoluted in their plots to be considered better than the first film. 2011’s On Stranger Tides brought the franchise even lower, feeling unnecessary and frankly rather boring as a whole. Now, Captain Jack returns for what might be one final gasp to save this tired franchise. There is some hope behind this film project. Acclaimed Norwegian directors Joachim Ronning and Espen Sandberg, who won raves for their sea based adventure Kon-Tiki (2012), have taken over the reigns of this franchise, and have promised to put more emphasis on in camera stunts over CGI extravagance. The casting of Javier Bardem as the villainous Captain Salazar is also a good thing, and I’m pleased to see Geoffrey Rush returning as my favorite character in the series, Barbosa. On the other hand, Depp’s schtick as Jack Sparrow may have worn out it’s welcome over the years, and it might be time to put the character finally to rest. I hope that this is an adventure worth taking, but my worry is that it’s one ride that no longer thrills.

ALIEN: COVENANT (MAY 19)

Ridley Scott has certianly never been a director to rest on his laurels. Even into his late 70’s, he is still continuing to churn out film after film, working in all sorts of different genres. His new feature finds him on familiar ground, returning to the franchise that he helped to launch back in 1979 with the iconic Alien. In 2012, he tackled the franchise again, only this time exploring the origins behind the titular monster with Prometheus. Prometheus received a mixed reception from fans and critics, some calling it too self-indulgent and not exciting enough to carry the Alien franchise into another chapter. I for one was okay with the movie; it was neither a franchise highlight, nor was it one of it’s lowpoints. It was a perfectly serviceable sci-fi picture. Scott returns now with what is possibly meant to be the linking piece between Alien and Prometheus in Alien: Covenant. My worry however is that after the two previous films, is there anything left for Scott to explore with this franchise. It seems like this movie is just retreading the same things we’ve seen before; watching each of the cast members being picked off one by one by the dreaded Xenomorph. It was terrifying in the first Alien, when Scott was breaking new ground, creating genuine scares that would influence a whole generation. Now, with too many tools at his disposal, I don’t know if Scott can do that again. At least he was able to let the atmosphere make Prometheus stand on it’s own. With Covenant, it just feels like we’ve seen this all before.

CARS 3 (JUNE 16)

It pains me to have to put low expectations on something from the Pixar studio, but I am less optimistic about their entry this summer. Truth be told, I thought the first film in the Cars franchise was a pretty good flick. Not Pixar’s best, but still a pleasing feature with a unique visual aesthetic. Unfortunately, Cars 2 holds the distinction of being Pixar’s first real failure. After a decade of nothing but glorious raves for all their movies, Cars 2 was panned across the board as both visually and narratively lackluster. The main problem is that it took the focus away from the first film’s central character Lightning McQueen (voiced by Owen Wilson) and shifted it to the obnoxious supporting character Mater (voiced by Larry the Cable Guy), putting him into a nonsensical spy movie plot. It seems that the filmmakers recognized the faults of the previous movie, and have sought to right the course of the series by putting Lightning McQueen back into the spotlight, but is it really necessary any more. It felt like his character arc was complete in the first film, so I don’t see what more they need to do with this franchise. My guess is that they’re going for a “one last hurrah” kind of story-line with this one, which to be honest may not be so bad for this series. It makes more sense than Mater the Spy from Cars 2. My hope is that Pixar doesn’t drop the ball with this one like they did the second time around, but again, maybe this is a franchise that’s better left off the track. For a studio as groundbreaking as Pixar, their efforts are placed elsewhere than trying to put a new coat of paint on a busted old car.

MOVIES TO SKIP:

TRANSFORMERS: THE LAST KNIGHT (JUNE 23)

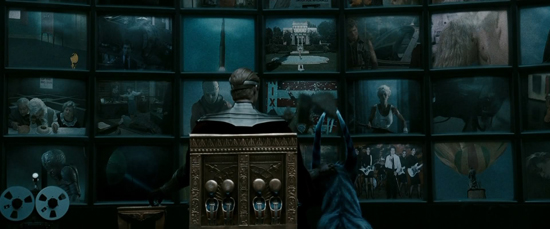

For some crazy reason, Michael Bay’s increasingly moronic and over-stuffed Transformers franchise still manages to keep going. Sure the franchise made a little improvement with the last film by swapping out Shia LaBeouf with Mark Wahlberg in the lead role, who is far more likable, but that was the only positive in the bloated mess that was Age of Extinction (2014). The franchise now reaches it’s fifth entry, and I am struggling to find anything left worth caring for in this series. The franchise resembles the original source cartoon and toy line very little now, and it still annoys me that the Transformers themselves are little more than supporting characters in a movie that’s supposed to be about them. What we’ve gotten instead is Michael Bay throwing every cinematic indulgence that fits his fancy, and it makes all of his movies (especially these ones) nothing but convoluted messes. What astonishes me about this one, however, is that he managed to wrangle in Anthony Hopkins for a role in the movie. Hopkins, who is arguably one of the greatest actors of his generation, is too good to be in something like this, so I don’t know what kind of magic Michael Bay worked to bring him on board. It might just be interesting to see how Sir Anthony does in this feature, but if it means that I’ll have to sit through nearly three hours of Michael Bay overkill just to get to his scenes, I don’t think it will be worth the effort.

THE MUMMY (JUNE 9)

In another desperate attempt to formulate a cinematic universe on the level of Marvel’s multi-franchise success, Universal Pictures has dug into their collection of movie monsters to build a collective universe around, to not as expected results. Their first attempt was the very bland Dracula origin story, Dracula Untold (2014), which released to indifference with audiences and critics. Now, it’s the Mummy’s turn to generate some heat in order to make their universe plans come to fruition. The makers of this film did manage to land Tom Cruise is a key lead role, as well as Russell Crowe in the role of Dr. Jekyll (yeah, Jekyll meets the Mummy; wrap your head around that logic), but it doesn’t make the film feel any more interesting. Like Dracula Untold, this movie just feels more like a studio mandate than an actual interesting story worth telling. I think that it is worth revisiting The Mummy as a story again, but when it’s tied to this cynical cash grab attempt by a studio, it feels less exciting overall. I would rather see something artistic done with the Mummy character, like a period piece or a more straight-foward horror remake. This just feels bland, boring, and a waste of time.

THE EMOJI MOVIE (JULY 28)

Proof that not every cultural fad needs to be turned into a movie. Now, truth be told, people scoffed at the idea of The Lego Movie (2014), and that film turned out to be a classic. But, what benefited Lego was a witty script that did a brilliant job of entertaining while never feeling like a feature length commercial, effectively just turning the product into a cinematic tool rather than a marketing one. This, however, looks to be nothing like that. I’d say that The Emoji Movie has more in common with the recent Angry Birds movie from 2016, which felt like a rushed film project made to purely capitalize on a cultural craze while it was still popular. I honestly don’t know where they can go with this project, and the trailer only indicates to me that all this movie is going to do is present a trivial story with a steady string of obvious visual puns. Of course, visual puns are what emoji’s are all about, but no one wants to see a feature length film that does that. Better to delete this unnecessary film out of any and all conversations in the future.

So, there you have my outlook on the Summer months ahead. I’ll be sure to give you my thoughts on the big titles as the season goes along, starting with Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2, which I plan to review next week. Hopefully all my must sees are worthy of the hype surrounding them, but also I would like to see a few of the ones that worry me exceed my expectations and end up being better than I anticipated. I’m pretty confident about where all these movies stand, but there have been years in the past when I’ve been way off. In any case, my hope is that the movies this summer not only perform well, but actually stand out as exceptional cinematic achievements as well. We’ve already seen some strong showings from the opening months of this year, so 2017 is already off to a good start. I absolutely want to be dazzled by Marvel’s expanding cinematic universe with Guardians and Spider-Man, as well blown away by Christopher Nolan’s unparalleled vision with Dunkirk, and be genuinely entertained by new efforts from the likes of Edgar Wright and Ridley Scott. At the same time, my hope is that some of the smaller fare this summer manages to shine through as well. It’s always worthwhile to see the next Ex Machina (2015) or Swiss Army Man (2016) shine through amidst all the noise of the summer season. In any case, I hope all of you have as much fun at the movies this Summer as I will. Let’s hope that all of us won’t be disappointed in the end.