What scares us the most as an audience usually differs from person to person. Any one of us could be scared of anything, from spiders to ghosts to even clowns. But, what ends up making us scared comes from a personal place and what baggage we bring with ourselves in everyday life. Fear is a personal manifestation of the feelings of rejection, revulsion, and anticipation that coagulate beneath the surface, and are triggered by an external force that brings all those feelings out at once. And the strange thing is that many of us like the feeling of being scared, as long as we know that we’ll be alright in the end. That is the feeling that Hollywood seeks to exploit when they try their hand at horror, but again, everyone’s fears are different. There are some instances when everyone’s fears do line up and it ends up driving the best of horror movies to great success. But, which example in the genre has managed to do that best. Well, given my own personal reactions, I can tell you that one of the most effective and interesting franchises to ever come out of the horror genre is the Exorcist series. The original film that started the franchise is of course an all time great, but what sets it apart, along with it’s follow-ups, is the effectiveness of it’s atmosphere and iconography. With it’s Gothic imagery, it’s almost oppressive use of darkness, it’s unrelenting look into the mind of pure evil, and it’s occasional use of shocking horrific moments, The Exorcist movies stand as probably the bleakest of all horror to ever come out of the Hollywood machine. It’s also a franchise that has not been immune to highs and lows in quality, but even that disparity between each installment is fascinating in it’s own right. In this article, I will be looking at the franchise as a whole (the good and the bad) and see how it has made it’s mark within the horror genre, as well as look at how the peculiar sidetracks it has taken over the years have made it one of the most unique horror franchises in the industry as well.

THE EXORCIST (1973)

Directed by William Friedkin

There are few if any horror films that can claim the kind of prestige that The Exorcist has. It is, without a doubt, a masterpiece of a film-making and an icon of the genre. But, why did this film perform as well as it did? To put it simply, it was a perfect example of everything falling into place at the right time, with a near flawless execution. The story is simple enough. A young child named Regan (Linda Blair), the daughter of a famed actress (Ellen Burstyn), suddenly begins behaving strangely at home, which then evolves into violent behavior. Soon after, supernatural events occur and it dawns on the mother that her child might indeed be possessed by something evil. She resorts to calling upon the help of a tormented priest named Father Karras (Jason Miller) who finds that the demon possessing Regan is no ordinary spirit but something far sinister and powerful, which then leads him to calling upon a renowned exorcist who has had a personal history with this particular demon; Father Merrin (Max von Sydow). What most people remember most from the movie is the now iconic Exorcism itself, as Fathers Merrin and Karras perform one of the most harrowing rituals every put on screen. This scene is chilling on it’s own, but it’s elevated even more by the exceptional building of tension that we’ve seen up to that point, watching poor Regan become tortured by the demon inside her, transforming her into a literal unholy monster. It stands out so much from horror movies before or since it’s creation, and that’s because of the “matter of fact” way it was staged. Director Friedkin, coming straight off his Oscar-winning success with The French Connection (1971), made the brilliant decision to shot the movie like a drama rather than a horror picture, and that perfectly heightens the terror on screen, because it feels so unnatural.

One thing you’ll notice about the movie is the brilliance of it’s stripped back aesthetic. The movie doesn’t rely heavily on jump scares, dramatic lighting, nor music cues to heighten the tension of the movie. It all builds naturally through the atmosphere in the movie, and seeing the slow degradation of Regan over time. In fact, despite having one of the horror genre’s most famous musical themes (courtesy of Mike Oldfield), the film is devoid of any background music, giving it a stark realism it might not otherwise have had. The cinematography also brilliantly conveys a natural, unfiltered dread as well. Shot with mostly natural, diffused light, the film has this coldness that permeates the entire movie. By the time you get to the exorcism finale, you have already been immersed in this moody, oppressive atmosphere long enough that you forget you’re watching a movie and instead feel like your seeing real life unfold; and it’s terrifying. The cast likewise brilliantly adds to the level of authenticity to the production. While veterans like Max von Sydow, Ellen Burstyn, and Lee J. Cobb all give exceptional performances, it’s Linda Blair in her breakout role that really makes the movie memorable. The fact that an actress of her young age had to endure such painstaking feats in order to make you buy into her possession, including the groundbreaking make-up by Dick Smith, is really something amazing. You see this little girl completely disappear into this demonic monster, and it is the stuff of nightmares. Whether she’s mutilating herself with a crucifix, twisting her head all the way around, or floating feet off of her bed, Regan’s presence on screen has come to define the genre since. Special mention should also go to actress Mercedes McCambridge, who went un-credited as the voice of the demon. Her gravely delivery further drives home the chilling transformation. The movie is considered a classic for all the right reasons, and it’s iconic status is rightfully deserved. Few other movies in the horror genre can claim to be half as effective or scary as this restrained masterpiece.

EXORCIST II: THE HERETIC (1977)

Directed by John Boorman

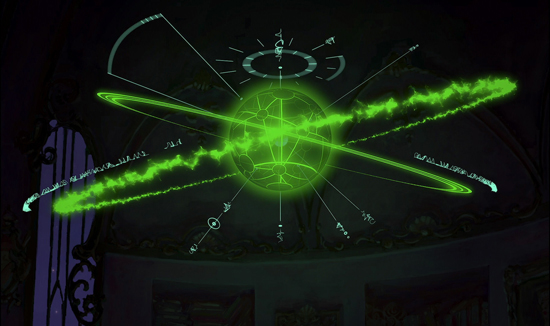

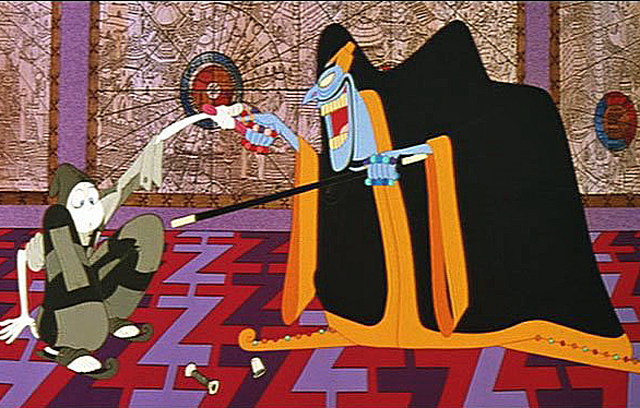

Everything about the first Exorcist was justifiably celebrated; the atmosphere, the performances, the direction, everything. But, what was most celebrated was the subtlety, and matter of fact-ness that it approached it’s subject matter with. Now, imagine a sequel that was devoid of all that subtlety, as well as lacking any restraint whatsoever. That is what we got with Exorcist II; not just one of the worst sequels to a horror movie ever made, but also one of the most baffling. Director John Boorman brought his own cinematic style, which tended to favor the surreal over the terrifying, which he honed on quirky cult classics like Zardoz (1974). While his style works just fine for films like Zardoz and later Excalibur (1981), it proved to be a terrible match for the Exorcist. Linda Blair returns as Regan, who is now seeking therapy worrying that the demon who possessed her is still there. She is also investigated by newcomer, Father Lamont (Richard Burton), who is seeking answers in the “spoilers” death of Father Merrin from the previous movie (Max von Sydow also returns in a few brief flashbacks). The movie sets much of the action with the mental clinic that’s treating Regan, and the overly stylized setting as well as the flashy way in which it is used points to exactly why this movie failed. It forgets exactly what made the original so terrifying, which was the show of restraint on the part of the filmmakers which heightened the realism. Here, Boorman wants you to notice his direction, and while the movie is at times beautifully shot, it is never in any way scary. The only redeeming value of the film is that it misses the mark so badly, that it can sometimes be hilarious to watch; but again that reflects terribly on it’s connection to the original. It’s flashy and garish, and in no ways feels like a natural continuation of the original. Richard Burton’s barely caring performance doesn’t help much either. It should’ve been obvious to John Boorman that a swarm of locusts doesn’t come anywhere near as being scary as a possessed child vomiting green projectile while strapped to a bed. And it’s a lesson in cinema showing that style cannot support moments of horror alone. the more natural approach it turns out makes a movie much more terrifying.

THE EXORCIST III: LEGION (1990)

Directed by William Peter Blatty

After the baffling embarrassment that was Exorcist II, the franchise went into dormancy for over a decade. Then, it found new life thanks to the efforts of the unlikeliest of saviors; it’s original creator. Screenwriter turned novelist turned filmmaker Blatty was the man who crafted the original novel on which the first movie was based on. When it came time to adapt The Exorcist’s literary sequel, conveniently titled legion, Blatty took it upon himself to not only adapt the book himself, but also assume duties as director as well. And remarkably, he proved to be quite adept at it. While, Exorcist III is not as perfectly executed as the first movie, it nevertheless feels much closer in spirit to it’s predecessor. It retains the right amount of atmosphere, it takes it’s story much more seriously, and it is genuinely terrifying at times. The film centers this time around the character of Lt. William Kinderman, the detective from the first movie who was played by Lee J. Cobb. Here, the character is played by George C. Scott, who does a commendable job of filling the late actor Cobb’s shoes. In the movie, he’s investigating a series of murders that bear the trademarks of a notorious serial killer called the Gemini Killer. Only one problem, the Gemini Killer has been dead for 15 years. The investigation leads him to a mental hospital where he finds a horrifying discovery; one of the patients is the once thought deceased Father Karras (Jason Miller returning to the role). Blatty’s film, whole not perfect, nevertheless does an excellent job of returning the franchise back to it’s roots. In particular, the atmosphere is spot on, and subtle in all the best ways. The movie also has what is widely considered to be the best jump scare in film history, which is a real testament to Blatty’s direction. But, the movie’s true best element is the unforgettable performance of Brad Dourif as the Gemini Killer, who we learn is possessing Father Karras alongside the demon from the first movie. Dourif is absolutely terrifying in the film, to the point of being hypnotic, and more than anything he is the reason this movie is worth watching. It took a long time, but this was the movie brought this franchise right back to it’s place as one of the most terrifying in cinematic history. Not bad for someone who literally wrote the book on this stuff.

EXORCIST: THE BEGINNING (2004)

Directed by Renny Harlin

The franchise would once again take a long sabbatical again until Hollywood would once again come calling. This time, however, the results wouldn’t turn out quite so well. But, strangely enough, this would also prove to be the most fascinating years out of the franchise because what we got was an unexpected experiment in film-making out of the Exorcist franchise that I don’t think anyone ever expected. Started by rights holders, Morgan Creek Productions, the series was about to look back in time and present the untold story about how Father Merrin became an exorcist in the first place. After the first director dropped out, the project was given over to writer turned director Paul Schrader; best known for his darker themed films like Affliction (1998) and Auto Focus (2002), as well as the screenplay for Taxi Driver (1976). Schrader faithfully executed the script he was given, but the producers had second thoughts when they saw his more cerebral approach. So, they chose to re-shoot the entire film under the direction of Renny Harlin, whose better known for his work in action films. This move didn’t exactly work out either, and the film unsurprisingly flopped. This movie, again, showed us exactly what doesn’t work in this franchise and that’s the lack of subtlety. Renny Harlin’s Exorcist: The Beginning is a loud, in your face gore fest that felt more akin to the style of it’s era rather than a natural continuation of the franchise. The scares are predictable, and it makes heavy use of some truly awful CGI effects. The only thing it shares with the other Exorcist movies is it’s name as well as the character of Father Merrin, this time played by a rather lost Stellan Skarsgard. Nothing is added by this film overall to the franchise, making it just feel like a shameless cash grab as a result. And for that, it marks a low point in the franchise, one which could have resulted differently, which we would soon could have happened.

DOMINION: PREQUEL TO THE EXORCIST (2005)

Directed by Paul Schrader

When we hear about re-shoots, we often speculate about an alternate version of a movie that we’ll never be able to see. Most of the time, a re-shoot happens to alter one or two scenes to help a struggling film feel more cohesive. Rarely do you see that happen to an entire movie, and even rarer do you see that alternative version make it to theaters as it’s own film. But, that’s exactly how we got this fifth installment in the Exorcist franchise; one that should’ve never happened in the first place. After Beginning’s failure at the box office, Morgan Creek realized too late that they may have made a mistake shelving Paul Schrader’s version and decided to give it a theatrical release of it’s own. Schrader was given the most minuscule of post-production budgets in order to finish his film, and while it does present something closer to his original vision, it still feels like one that is compromised. Still, Dominion does have one benefit, which is that it feels more in character with the spirit of the franchise. The film is interesting to watch alongside Renny Harlin’s version, because it shows how two different directors can take basically the same plot, which has Father Merrin investigating a submerged church in the Egyptian desert that’s built upon a pagan temple, and come up with a completely different feeling movie. While it still pales in comparison to the terrifying moments of The Exorcist and Exorcist III, it does much better at maintaining a sense of Gothic atmosphere that Renny Harlin completely ignored. Skarsgard also is much better in this version, bringing a lot more depth to the character of Father Merrin, as we see what evil drove him back into God’s service. Neither this or Beginning stand very strong as horror movies, but together they make for one interesting lesson in storytelling on film; contrasting Schrader’s more subtle approach with Harlin’s flashier one. Dominion did only slightly better among critics than Beginning, but it did receive some welcome praise from a high place, and that was from William Peter Blatty, who commended it as a film in the true spirit of the original. Regardless, it’s still something of a miracle that Dominion saw the light of day at all, even with a rather lackluster roll out by the studios. It’s not anywhere near the height of the franchise, due to it’s still lackluster story, but it at least made an attempt to feel like it belonged in the same family as it’s predecessors and not feel like a lame attempt to follow a trend.

So, while the results have been wildly incoherent, the Exorcist miraculously has become a franchise that still has legs many years later. The original of course is a timeless masterpiece that still manages to remain chilling even today. And Exorcist III has managed to climb out of the shadow of it’s predecessor and become a beloved cult hit in it’s own right. The best thing though is that you don’t have to watch the whole of the series in order to appreciate it’s finer parts. The first and third installments stand perfectly well on their own apart from their lackluster follow-ups. Exorcist II basically serves as a bizarre cautionary tale about how not to make a sequel, and the two back to back prequels offer an interesting look at how a movie can differ so greatly depending on who’s directing it. But, personally for me, I admire The Exorcist franchise (at it’s best) for taking it’s scares seriously and not exploit them for shock value. I grew up in the Catholic church, so some of the themes and iconography were all very familiar in the films. As I’ve grown older, my views on religion have changed significantly, but at the same time, it’s still be a part of me, and it’s what follows me into my experiences viewing these movies. It’s my own kind of baggage that these movies prey upon to bring out my fears, and that’s probably why I find The Exorcist one of the most frightening films ever made. For me, it brought out my worst fears, of losing my soul as well as control over my own self, and that’s what keeps it resonating for me so many years after viewing it for the first time. I still marvel at the incredible seriousness that the movie takes with it’s subject, which as we’ve seen can be mishandled to the point of silliness in other films. The Exorcist franchise is horror film-making taken beyond the point of simple scares, and into the realm of creating genuine dread. Exorcisms may not in fact be a real thing, but these movies have sure convinced us all that they could be. Nothing is scarier than feeling the sense that our worst fears can manifest into real terror, and The Exorcist managed to turn that kind of fear into high art and an unforgettable experience.