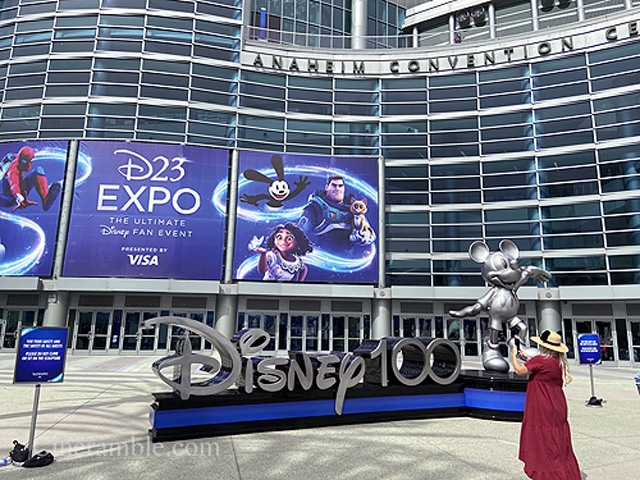

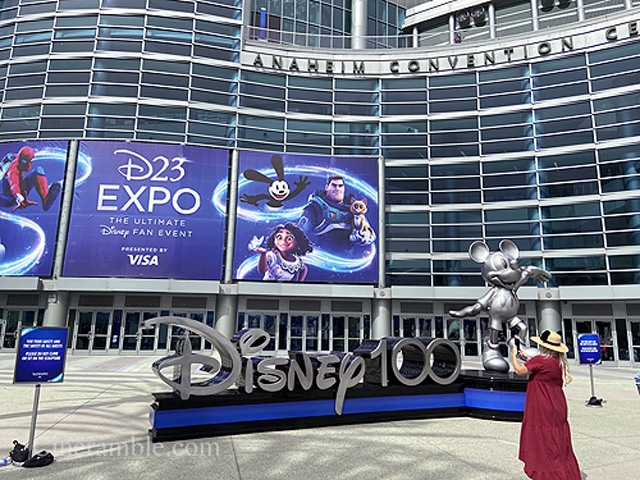

It’s been a long break for the D23 Expo. The ultimate fan event for all things Disney has been on a bi-annual schedule until the Covid-19 pandemic made it impossible for most large gatherings to happen. Though scheduled initially for 2021, the continuing surges of that year convinced Disney to delay their marquee event for another year, pushing it into 2022. Now with the pandemic thankfully heading into the rear view, at least with regards to major outbreaks, Disney is ready to invite it’s most dedicated fans back to the halls of the Anaheim Convention Center for it’s 7th D23 Expo celebration. I have been covering the Expo since my first year writing this blog back in 2013, and I have been eagerly awaiting to return. Just like having the TCM Film Festival back after a long pandemic hiatus, this is yet another movement for me back to having things back to normal, and I’m sure the same thing is felt for a lot of other dedicated Disney fans. Apart from moving past the pandemic, this D23 Expo is also coming to us at a very important time in the history of the Disney company. For one thing, Disney is using this Expo to kick off what will be a multi-year celebration of The Walt Disney Company’s 100 Year anniversary. The namesake of the D23 fan club is the year the the company was officially founded; 1923. Disney certainly wants to mark this milestone with a lot of pomp and circumstance and the Expo we are going to see this weekend will hopefully be a great representation of that. This Expo also sees the company in transition, trying hard to rebuild itself after a shaky pandemic affected blow to it’s theatrical and theme park business. This will also be the first Expo of the Bob Chapek era, the new CEO and successor of Bob Iger, the former head of the company who oversaw the launch of D23 and the Expos. There’s no doubt about it, this is going to be a D23 Expo that will have a different air of importance than those of the past, and that puts a much brighter spotlight on it than we’ve seen before.

I am once again attending all three days, and I’ll be sharing my day by day account of all the sights and sounds that I’ll see there; complete with my own pictures. I’m going to try my best to get into the big shows; the Animation panel, the Live Action panel, and the theme parks panel being the most important. I will also try to find interesting smaller panels across the weekend as well, while at the same time hopefully getting a good in depth look at all the different booths on the show floor. There are going to be archive exhibits across the Expo that I also want to check out, and most intriguingly Disney is also bringing Walt Disney’s private jet to the Expo, giving it a showcase all it’s own in an up close look for all the Expo attendees. It will also be interesting to see how fans of all things Disney will react to all the future plans that the company is going to showcase at this Expo. Beyond just Mickey Mouse and company, Disney is home to a wide array of brands; Marvel, Star Wars, National Geographic, ESPN, Hulu, and 20th Century Studios. This will be the first major Expo since the finalization of the Fox merger, so it will be interesting to see how much of a presence the 20th Century brand now has at this Expo. Regardless, I’m ready for a long three day adventure. Below, you’ll find my account and final thoughts, and I hope to have this published as soon as I can. With that, let’s take a trip to D23 Expo 2022.

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2022 (DAY 1)

Like I have in year’s past, the key part of my plan to get the most out of my D23 Expo experience is to be extra prepared. So, I started off the beginning of my event experience with leaving my hotel room very early in the morning in order to line up at the security gate to enter the Anaheim Convention Center. Even at 4 am, the line to enter was pretty significant. Though Disney clearly stated that this time there would be no overnight queuing, people still showed up well before the 5 am gate opening. We were let in and allowed to wait for the official opening in the underground Hall E, which is where the queue for the big Hall D23 shows would be. One of the new things this year that they introduced was a randomized Show Pass system. Each attendee had the opportunity to select a ranked selection of shows and experiences that they wanted to have a pass for, which guarantees them a seat or place in line. Obviously the big Hall D23 shows were the most sought after. I always try to hit the big three (Animation, Live Action, and Theme Parks), and this year I managed to snag a reservation for the Friday afternoon show, which was the Animation Presentation. Because of this, I really had no need to show up so early, but I decided to do so anyway because it gave me a chance to see how these shows were going to be lined up and seated throughout the Expo. There was a line-up for people to see the first show of the Expo, the Disney Legends induction ceremony. This year, Disney was honoring the new inductees into their hall of fame style Legends pantheon, which included Frozen (2013) cast members Josh Gad, Jonathan Groff, Kristen Bell, and Indina Menzel; Enchanted star Patrick Dempsey, and the late Chadwick Bosemen of Black Panther (2018), honored posthumously. I haven’t attended this show before and had a better opportunity this time with my reservation, but I instead decided to dive right into experiencing the show floor itself.

At 9am, the doors opened for us and I got to be among the first to see the floor first hand. The spacious floor was again filled with massive booths for all things Disney. The first thing in front of me was the Marvel booth, which looked much like it has in years past, with a large space designated for fan congregation, as well as a stage and a place for talent and fan interaction. One fun new thing they added was a photo opportunity in the back themed to the AvengerCon seen in the Disney+ series Ms. Marvel. Beyond the Marvel booth was a Lucasfilm booth, with of course Star Wars being the centerpiece attraction. The whole Lucasfilm booth was more of an exhibition this time, with costumes on display from their recent and upcoming projects. There were costumes from The Mandalorian TV series, as well as the recent Obi-Wan Kenobi mini-series, and the upcoming Andor series for later this month. In addition to Star Wars, there were costumes on display for other Lucasfilm properties, such as the upcoming Willow Disney+ series, and of course Indiana Jones. Seeing the Indiana Jones costumes up close was especially neat, as they span across the series, with Harrison Ford’s iconic ensemble, to a costume from the villainous Toph in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s costume from the upcoming movie. Across from that was the expansive Disney Bundle pavilion. Here the showcase was for all the streaming services under the Disney banner, which includes Disney+, Hulu, and ESPN+. Disney+ of course occupied the largest footprint here, with a full presentation stage of it’s own that hosted special discussions throughout the Expo. The Hulu and ESPN+ booths were smaller and on the edges, but still offered some fun photo opportunities for fans. I didn’t spend too long here, although there was a fun little foot-pad experience that showed off a neat shadowbox projection effect, promoting current and upcoming Disney+ programming that was worth trying. What I had my sights on next was one of the biggest and most interesting exhibitions in the entire Expo.

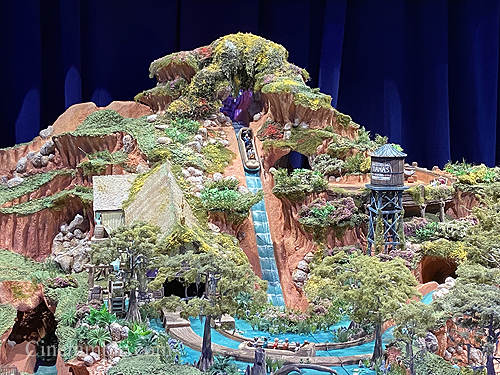

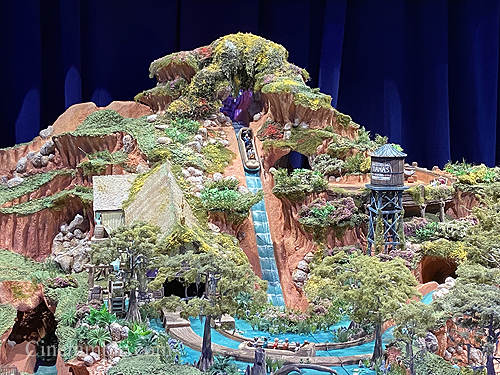

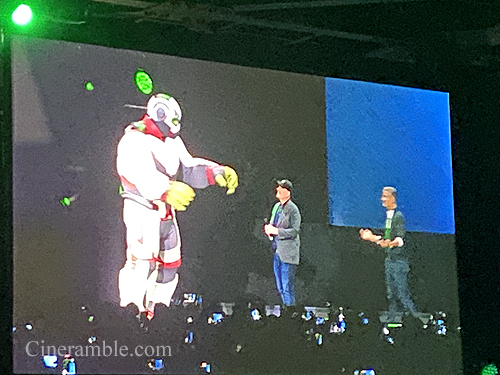

In the southernmost side of the convention center was the Wonderful World of Dreams exhibit, which was the one that was put on by Walt Disney Imagineering. This is where the Disney company showcase all of the projects they have currently in the pipeline for their theme parks and vacation destinations. This particular exhibit, I have to say, is the most impressive and largest one yet seen at the D23 Expo. It was a sprawling set-up, well laid out with exhibits separated into the different theme parks around the world. First up in the gallery was the newest park Shanghai Disneyland, which spotlighted the upcoming expansion it will be adding based on the movie Zootopia (2016). They showed some concept art and models of potential rides coming to the park, but what was also included was a fun demonstration of the street atmosphere. Occasionally, live performed puppets of Zootopia would open up doors in the wall and begin interacting with each other. If this is a taste of what is to come, the Shanghai Disneyland guests are in for a definite treat. Next, there were small exhibits for the other international Disney Parks in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and Paris. What was spotlighted in these were new attractions dedicated to the movie Frozen, with Tokyo’s ride being part of an expansive Fantasy Springs expansion to their Tokyo Disney Seas theme park. Of course, the largest room was dedicated to the two theme parks central to the company, those being Walt Disney World in Florida and Disneyland in California. On the Disneyland side, they had displayed models of their current Mickey’s Toontown re-imagining, which will include the new ride Mickey and Minnie’s Runaway railway, housed in the hilariously named El Capitoon Theater. In the Walt Disney World section, there was a replica of the new founder’s statue of Walt Disney that will be installed soon in Epcot. In the middle of this space was a model of a project coming to both parks, which is an upcoming re-imagining of the Splash Mountain ride with characters from The Princess and the Frog (2009), which is named Tiana’s Bayou Adventure. The next room was an interesting look at the tech they are working on in the parks, which includes a new type of character interaction technology for large characters, such as Marvel’s Hulk. The last exhibit was devoted to Disney Cruise line, which included looks at their new ships and destinations. A full and very satisfying exhibit worth multiple viewings.

After walking around for a while, it was time to start seeing some shows. With my reservation, I was granted a bit more time on the first day to do whatever I wanted, so I decided to check out one of the smaller shows at the Expo. Available at what they called the Premiere stage was a presentation devoted to Disney and Marvel video games. I managed to get a chair way in the back for this one, but I wasn’t able to watch the whole show, because I had a conflicting reservation. Suffice to say, it was a Marvel heavy collection of games with a couple of cute Disney ones here and there. But it was neat seeing the new Premiere stage, which is debuting at this year’s Expo, housed in the convention center’s new expansion. Quickly making my way to the underground Hall E, I only had to wait an extra 30 minutes to be seated for the Hall D23 Animation presentation, a welcome change from year’s past, which had me waiting hours prior to show time. Spacious Hall D23 looked as grandiose as I remember it, and after 3 long years, it was great being back. The presentation started with a montage celebrating all the media that the Disney company has put out in the last couple of years, and it concluded with the premiere of the brand new Disney 100 logo that will play in from of all their upcoming movies both in theaters and on streaming. Then, onto the stage walked actress Cynthia Erivo, who most recently starred in Disney’s live action remake of Pinocchio (2022), playing the Blue Fairy. After a round of applause, she began to sign her rendition of “When You Wish Upon a Star” which was very lovely. Afterwards, newly promoted Walt Disney Pictures president Sean Bailey walked out on stage and welcomed the crowd. He promised plenty of new surprises in the show we were about to watch.

The first selection of films presented were a few Disney+ exclusives, which included Hocus Pocus 2 (2022) and Disnenchanted (2022) with which the entire cast was there to promote. Once we got to the theatrical set of projects, we learned that we were getting a new Haunted Mansion movie. This cinematic reboot is being directed by Justin Simien, who brought with him a first look at the movie. Afterwards came one of the show’s highlights, which was the announcement of who would be playing Madame Leota. A Doombuggy ride vehicle rolled onto stage, spun around, and revealed to the audience Jamie Lee Curtis, who waved happily at the cheering audience. Disney concluded this live action segment talking about upcoming remakes of their animated movies. One was Snow White, starring Rachel Zegler and Gal Gadot as Snow White and the Evil Queen respectively who were both in attendance. The other was The Little Mermaid, which director Rob Marshall showed us a full 4 minutes of, that being the whole “Part of Your World” sequence. Afterwards, the actress playing Ariel, Halle Bailey walked on stage to thunderous applause.

Next, was the Animation portion of the presentation. First up, Pixar Animation, which has honestly had the roughest couple of years during the pandemic, with most of their movies going straight to streaming. Pixar Studios head Pete Doctor walked out to tell us about the exciting new projects they’re working on. The first one shown was next summer’s release Elemental (2023), which was best described as Pixar’s first rom com, but with their usual twist on established formulas. Here, the characters are made of actual elements, with the main characters being literally made of fire and water. We were shown a few test animation samples, as well as a few quick scenes of the movie. Finally they introduced us to the voices of the two leads, Mamoudou Athie and Leah Lewis, who were accompanied onto stage with actual fire and water rising from the stage and falling from the ceiling. It was a neat theatrical trick to add some panache to the presentation. After the showcase of Elemental, Pete Doctor began to discuss the first original long form series by Pixar for Disney+, called Win or Lose. The show is going to be about a week in the life of a little league baseball team, and each episode will tell the story from a different character perspective. Lastly, they announced the follow-up film to Elemental called Elio, which is about a shy kid who is abducted by aliens and must be a representative of Planet Earth in the cosmos, despite struggling to fit in even when he’s living at home. The visual development stuff that they showed us looked really interesting and it definitely peaked my interest to see how this film turns out. As a special surprise, Amy Poehler walked out onto stage to officially announce that Inside Out 2 is in the works, while at the same time playfully chiding Pete Doctor who wanted to keep things more secret.

Finally, the presentation ended on Walt Disney Animation, the bedrock of the company which is also celebrating 100 years. We were shown a glimpse of the upcoming Disney+ series Zootopia+, but most of the focus was on the upcoming fall release of Strange World (2022). The film’s director and writer, Don Hall and Qui Nguyen, were joined on stage by a few of the cast members of the movie, including Jake Gyllenhaal, Jaboukie Young-White, Dennis Quaid and Lucy Liu. After a short talk, we were presented an extended scene from the movie. It was an engaging moment that gave a good sense of the movie, and thankfully we don’t have to wait long for the rest. Finally, the show ended with the announcement of Disney’s special 100th anniversary release. In this one, they are imagining the origins of the Wishing star seen in so many of their movies. So, the movie is conveniently titled Wish. In it, we meet a princess named Asha who befriends a literal star. Asha also has a pet goat named Valentino, who is going to be voiced by Disney lucky charm Alan Tudyk, who was there to demonstrate his many roles live. To close out the show, we were presented a special debut of one of the songs from the movie, sung by the actress playing Asha, Oscar-winner Ariana DeBose. Overall, a pretty eventful show with a lot of exclusive looks. I was especially happy to see Disney committing more to theatrical releases with some of their titles, and not just dumping them onto Disney+. So, a little more walking around for an hour and Day one came to a close. Unfortunately, Southern California was getting a brush by from Hurricane, which led to us exiting the convention center in pouring down rain, right on the heels of a heat wave no less. Thankfully, I packed an umbrella and it was off to rest in my hotel for Day 2.

SATURDAY SEPTEMBER 10, 2022 (DAY 2)

This was the day that was really going to test my preparedness for this Expo. I left my Hotel very early, and not surprising very few people were honoring that 4:30 am rule. Arriving a little before 4:00, I found the line to already be substantial to get in. Once the gate finally opened, I’d say the line to get in probably stretched all the way down the block, though I couldn’t quite get a confirming look. Why was it so busy you might say? Because the Saturday Morning show, always the busiest of this Expo, was the one where Marvel and Star Wars were going to present their upcoming projects. Suffice to say, I wasn’t just contending with Disney fans here. I had to go up against two other rabid fan bases. Once through the gates, we quickly made our way to Hall E to queue up. Even as early as I got there, and as much as I rushed, the line still filled up quickly. I had no reservation for this show, so I had to contend with stand-by, which itself filled up. Thankfully, I made it before they closed stand-by to anyone else. But even here I had no certainty. I was put in what was essentially the standby of the standby; the distinction being who made it early enough to get a wrist band. After hours of waiting, the queues were finally walked into Hall D23. I watched as the regular standby managed to get in, and one line of the standby standy’s. A cast member made a head count and I got #53, hoping that it was a good sign I might get in. Alas, another cast member broke the news that the show was full, and that we had to exit the queue. So, for the first time ever, I struck out getting into a Hall D23 show, and it was the one I was most looking forward to. Dissatisfied, I walked back to the floor hoping to cheer myself up. I saw there was another presentation in one of the other halls running at the same time, and I managed to easily find a seat. This one was about the Disney 100 exhibition that was going to be launched next year in museums across the United States and internationally as well. It was an interesting break down of a neat exhibition that I hopefully may one day cover for this blog. It will feature a collection of artifacts from across the spectrum of Disney history. I just wish I had seen this show without the crushing blow of missing the Star Wars/ Marvel presentation. From what I understand, there weren’t a whole lot of internet breaking announcements made, so maybe it wasn’t too bad of a loss. I also got a nice Disney 100: The Exhibition poster after the show, something that I otherwise wouldn’t have gotten if I hadn’t been there. From what I understand, the big Hall D23 presentation only gave out posters as well, plus 3D glasses to watch clips from James Cameron’s Avatar: The Way of Water (2022).

With the extra time freed up, I decided to take the opportunity to visit one of the marquee attractions of this Expo; an exhibit dedicated to showcasing Walt Disney’s Private Plane. Dubbed Mickey Mouse One, the plane itself was flown in from Orlando where it had been parked for years at the Disney Hollywood Studios’ backlot. It received a refurbishment and was presented here at the Expo, making it by far the largest Disney artifact on display here. It not only needed it’s own room, it was presented in the Anaheim Convention Center’s spacious arena, which in the past had been used for 2nd-tier panels; the ones below Hall D23 in importance. Though guests couldn’t get up close to the plane, they did have a roped off area close enough to get some good picutres, including a special overhead shot that the Expo provides for everyone in line. After getting my photo, I checked out a bit more of the nearby gallery. In it, there were other artifacts from inside the plane like a passenger seat, some of the catering materials, as well as special baggage and paraphernalia that Walt gifted to guests who rode with him in the plane. The whole exhibit was nicely set up, and it made good use of what usually was show space. Literally as you walk right into the exhibit, the nose of the plane is staring right at you once you go through the doors. The exhibit also played some era appropriate ambient music, which really set the scene nicely for the kind of time period that Walt would have been flying around in this plane.

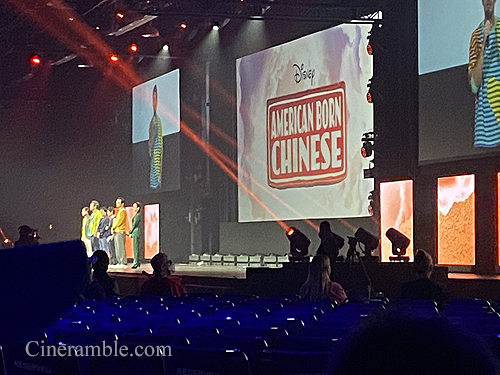

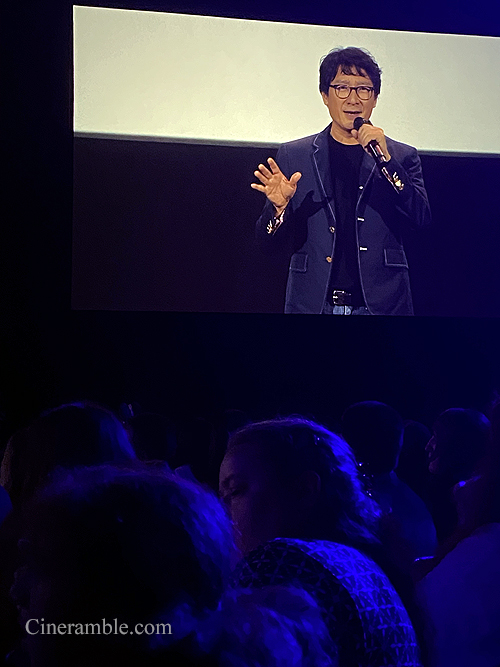

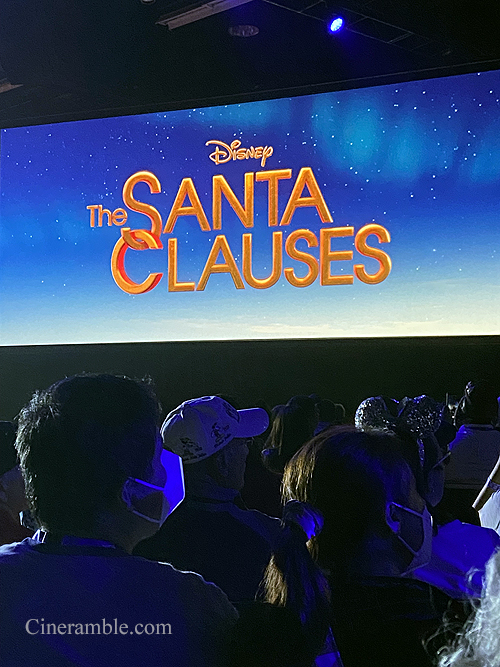

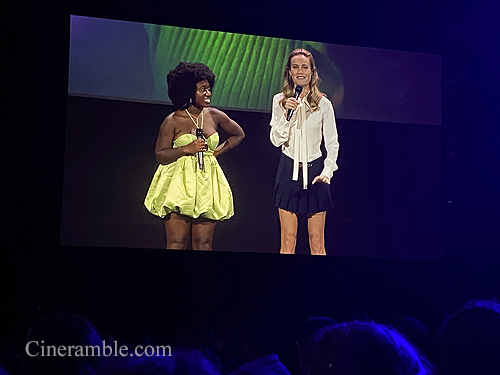

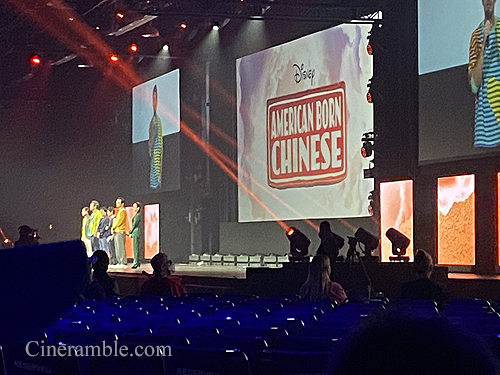

Still, I was determined to not leave the floor that day without at least checking out something in Hall D23. Unfortunately the afternoon presentation was for Disney Branded Television. This primarily encompasses original TV shows that fall outside of the major studio brands, so it was pretty much a lot of Disney Channel and a couple Disney+ kid-friendly shows; stuff that I honestly care the least about with the Disney company. But, I was willing to give the show a fair break. There was no problem getting in through standby, and the Hall unfortunately only filled half up, which made me feel bad for the special guest and performers on stage. While most of the stuff they showed was very uninteresting to me, like most of the Disney Channel programming and original movies such as Zombies 3 and High School Musical: The Series, there were still a couple nice surprises. First, the show opened with a special appearance from a few Muppets. And not just any Muppets, we got Dr. Teeth and the Electric Mayhem, there to promote a new Muppet variety show for Disney+. They led off with a rousing rock song which honestly helped to improve my mood immediately for the show. Another wonderful surprise was a presentation for a live action fantasy show called American Born Chinese. The show itself was intriguing enough, and they did a neat traditional dragon puppet dance on stage. But what made the presentation for this show even better was meeting the cast members. They included not one but two of the stars of the breakout hit film from this year, Everything, Everywhere, All at Once (2022), those being Michelle Yeoh and Ke Huy Quan, who earlier in the day got to be part of a now viral photo with his Temple of Doom co-star, Harrison Ford at the morning Hall D23 presentation. Also on stage was the show’s producer, Daniel Destin Cretton, who himself also has made news recently being selected to direct the next Avengers movie, The Kang Dynasty. There were also a couple of other special celebrity sightings, including Disney Legend Tim Allen, who was there to promote his upcoming series, The Santa Clauses, based on his series of hit movies. Captain Marvel herself, Brie Larson, was also on hand to present a look at a documentary series that she’s producing for Disney+. I will say that despite my cynicism for the stuff being presented and the sour mood I had going into the show, the showcase was still entertaining. The dancers they had throughout the show really put their heart into their performance, so I have to applaud them for that. Still, Day 2 was not my best at this Expo, and missing out on the big show sadly cast a pall over my day. I can’t blame Disney for that. They only had enough seats, and my number came up just short. For me, it was leaving me with reconsidering how I should plan for these days going forward. With so many seats being taken up by reservations, the rush for standby is very competitive now. Unfortunately, I had one last chance to get into the show I wanted, and I had no guarantee of getting into that one either.

SUNDAY SEPTEMBER 11, 2022 (DAY 3)

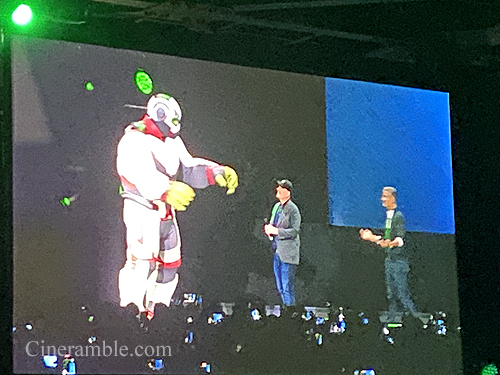

In the past, I have seen that the Sunday morning show, which almost always is theme parks, doesn’t fill up as fast as the Saturday morning show. Still, I was taking no chances. I arrived in line about the same time as I did for Saturday, and again it was a substantial line waiting for me. Already I grew nervous, and was keenly looking at how fast they could get us through the gates, and how quickly I could rush my way there. So, once the gates opened, and I went through the security checkpoint, I speed walked my way down to Hall E. Thankfully this time I got there soon enough to receive a regular standby wristband, but as I observed before, anything could happen. My anxiety rose even further as they seated everyone pretty late. The 10:30 am presentation began pretty much on time, and yet I still saw about half of even the reservation seats still waiting to be let in. Thankfully they got through all the reservation seats, so it was left to standby next. By this time, the Disney Parks president, Josh DiMaro, had already welcomed actor and filmmaker Jon Favreau on stage. About 10-15 minutes into the show proper, they did finally walk us into the Hall, so thankfully I wasn’t let down two days in a row. Sadly, Favreau’s segment was already over and he was already off stage, but the next guest was just as big, if not more; Marvel Studios chief Kevin Feige. He shared details about the new Avengers attraction that was coming to Disney’s California Adventure, which includes a storyline tied into the current Marvel Multiverse Saga. In the ride, the characters will be battling a new multiversal villain known as King Thanos. This new ride promises to feature a wide array of characters across the Marvel multiverse, though details of the ride system used were vaguely hinted at. Next, Feige and DiMaro were interrupted by a video message from Mark Ruffalo, who asked when we would see the Hulk in the parks. As it turns out, we got our answer as a fully built costume of the Hulk, built with the Project Exo technology shown in the Imagineering gallery, walked onto stage. The size of this character was truly impressive, and it will be interesting to see it in action up close in the parks, which DiMaro told us was happening in a week.

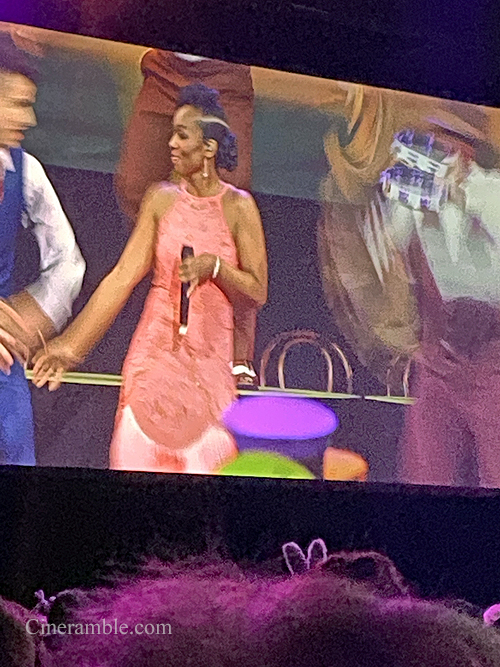

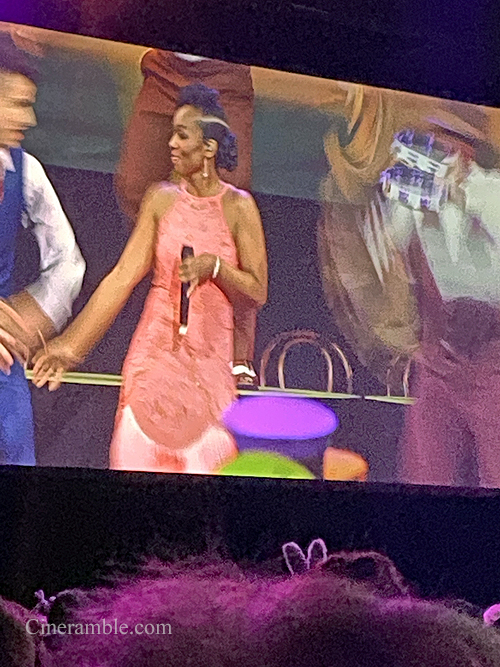

They continued the Parks presentation talking more about the big projects currently being worked on. One was the Mickey’s Toontown re-imagining, which I saw the model of in the Imgaineering exhibit, as well as the Princess and the Frog changes to Splash Mountain. One of the cool things that they did for all of us as we walked through the doors into Hall D23 was that we all got a silk handkerchief with the logo for Tiana’s Bayou Adventure printed on it. After they talked about what they planned for the ride, the team behind the ride asked us to take out those handkerchiefs and swing them over our heads in a New Orleans fashion as they welcomed a surprise musical guest, the voice of Princess Tiana herself, Anika Noni Rose. She performed two songs from from the movie with a back-up dance troupe on stage with her, and the audience responded with enthusiastic swinging of those white handkerchiefs. Josh DiMaro then moved on to news about the expansion coming to the Downtown Disney shopping and dining district in California. He shared the exciting news that Porto’s, a very popular bakery in the Los Angeles area, would be opening a new location there. To celebrate the news, he added that everyone in the Hall D23 audience would be leaving with free pastry samples courtesy of Porto’s. Afterwards, the focus went to projects going on in the international parks. We got to see a look at a Zootopia themed expansion coming to Shanghai Disneyland, and they also talked about the Frozen themed lands that are coming to the Tokyo, Hong Kong and Paris parks. Next, DiMaro went into a presentation of Blue Sky project ideas that are floating around the halls of Imagineering at Disney. These include attractions themed to Moana, Zootopia, Coco, Encanto, and the ever popular Disney villains. It remains to be seen if any of these project become a reality, but I think part of the reason they were shared here was mainly to gauge fan interest. They also talked about Disney Cruise line and the addition of their 6th ship into the fleet, called the Disney Treasure. Finally, they concluded with news of brand new nighttime shows coming to the Disneyland Resort to celebrate the 100th anniversary. It includes a new World of Color show at Disney’s California Adventure, as well as a new fireworks show at Disneyland. The show ended with a performance of the song that will accompany the Fireworks show, and we all exited, lining up eagerly to receive our individual boxes of Porto’s.

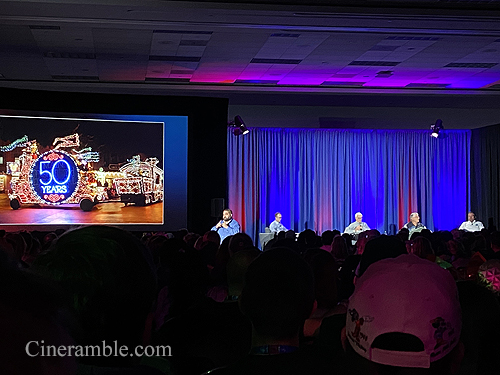

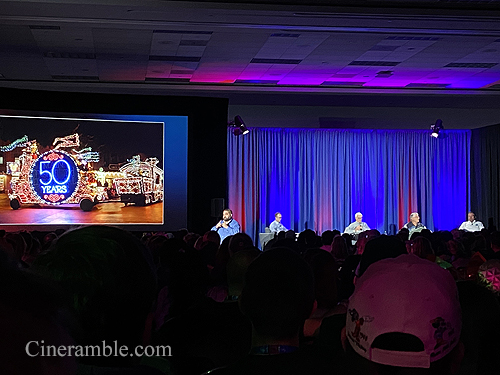

Having managed to get into the show I wanted, and getting a tasty treat out of it too, my morning mood was much better this day. And honestly, it kept being positive for the rest of this final day too. I had a really good final day at this year’s D23 Expo, and that helped to salvage it from the disappointment of Saturday. I decided to catch at least one more panel on this day, which was going on at the Walt Disney Archives stage on the second floor of the convention center. This panel was about the long running Main Street Electrical Parade, which this year was celebrating it’s 50th anniversary at Disneyland. I had been catching it myself all throughout the Summer, thanks to my annual pass. But, this panel offered an in depth look at the history of the parade, which honestly was far more fascinating than I had imagined. I forget the names of those involved, but they had the show director there, as well as the composer, and the current lead at Disney Parks entertainment who was responsible for the recent revival. They discussed a lot of interesting tidbits about the ride’s history, from it’s inception, to it’s disastrous rehearsals, to all the additions that have been made and since retired over the years. One of the most interesting stories was that the original composer of the parade’s them, “Baroque Hoedown” had his music sold to Disney by his agent without him knowing, and he only learned about it after having visited the park himself and hearing his own tune playing during the parade. It’s smaller shows like this that I think are the special little treasures one can discover while at the Expo. If you are not interested in competing for a spot in the Hall D23 shows, then these are perfectly good and worthwhile shows to check out too, not to mention also fascinating in their own right.

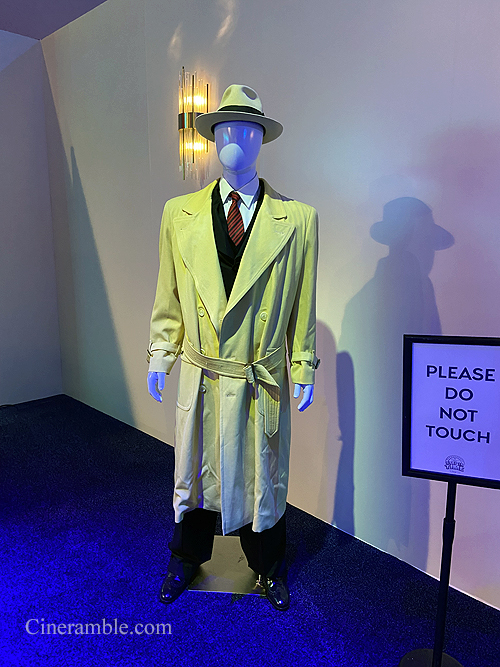

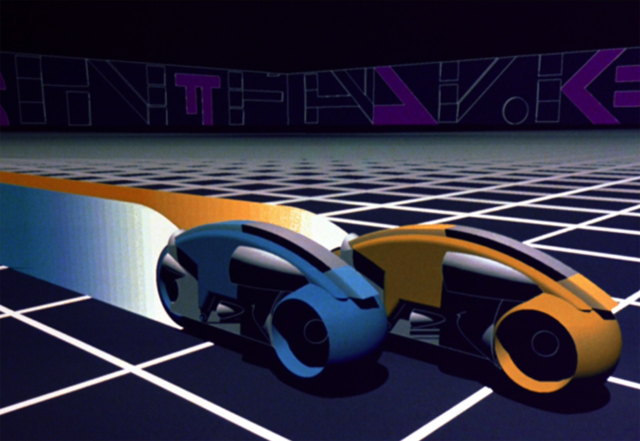

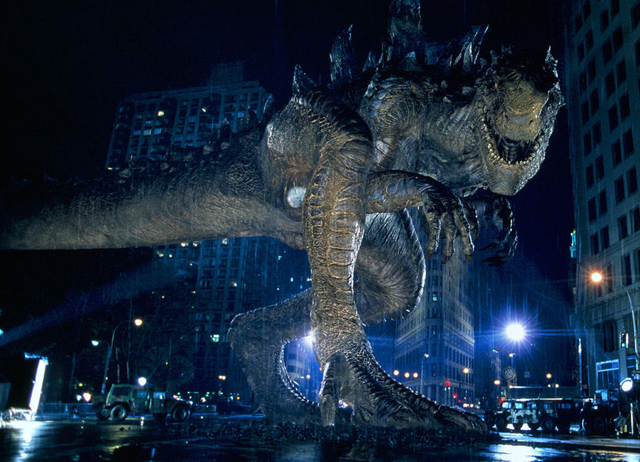

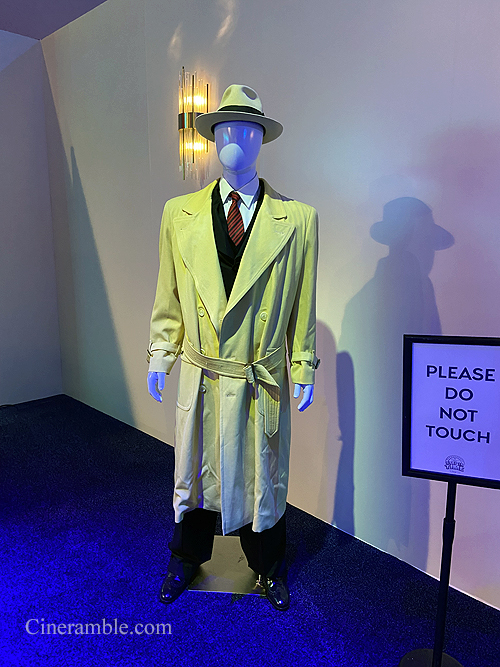

The rest of my day was spent playing everything else by ear. I made a visit to the Archives Gallery this year, which to be honest was a bit underwhelming compared to years past. This Disney 100: A Step in Time exhibit was basically laid out like a walkthrough timeline, with different spaces devoted to important milestones in Disney history. There were a couple artifacts found there, but mainly each section was more or less a photo opportunity spot, and not much more. The first spot was for the premiere of Mickey Mouse in Steamboat Willie (1928). The next was devoted to the premiere of Walt Disney’s first feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937). Afterwards, there was a spot dedicated to the opening of Disneyland in 1955, which did have the neat artifact of Disneyland Ticket #1, which was purchased by Walt’s brother Roy for $1. The next section spotlights the classic Mary Poppins (1964), had two of the carousel horses used in the film, as well as a dress worn by Julie Andrews. The next section was devoted to the opening of Walt Disney World, and they showcased a mock-up of the attic scene in the Haunted Mansion attraction to spotlight it. The next section was a surprise as it spotlighted the movie Tron (1982), celebrating 40 years this year. Some of the props from the movie were displayed here, as well as a replica of the neon Flynn’s arcade sign. The next room was likewise another surprise, as it spotlighted the film Dick Tracy (1990), complete with the iconic yellow coat and fedora that Warren Beatty wore in the movie. Finally, and not surprisingly, the last room was devoted to Star Wars, a recent addition to the Disney family, and in that section, they had full size replicas of all the droids: C-3PO, R2-D2, BB-8, and D-O. Layout wise, it was very well put together, but I wanted there to be more substantial things to look at inside, and not just backdrops to make for good Instagram posts. But, that was the only downside to my day.

I spent much of the rest of my D23 shopping and soaking in the atmosphere while I was still allowed in the Halls. And it was in these closing hours that I really got to appreciate what makes these Expos such a great experience each year. For one thing, I just loved spending hours meeting strangers throughout the day and sharing our common love for all things Disney. That community experience is especially what makes this worthwhile. While waiting in line for the Steps in Time gallery, I just struck up a conversation with the two ladies in front of me in line, who were dressed as Disney Princesses, but with pajamas on. Just by complimenting their costumes and speaking with them about their experience thus far, they shared that they came to the Expo the day before dressed as Princess Ghostbusters. It’s little things like that, people sharing their fandom in a three day fan event that I love every time I go there. Yes, I felt pretty down on Saturday by missing the show I wanted to see more than any other, especially knowing that it included a first look at the next Indiana Jones movie, with Harrison Ford on stage to present. But, my overall experience was still a positive one, especially with Sunday going as well as it did. As I made my way into the final hour, I just made my back through my favorite parts of the Expo, like the incredible Imagineering gallery, the small vendors Emporium, the Animation pavilion, which had been updated with the new announced projects from this Expo. I could honestly feel it from all the other guests, we were sad to say goodbye after such a fun time, but also grateful to have this back after a painful, pandemic delayed absence. Hopefully, they are back to their bi-annual schedule again, and barring any other calamities, we will hopefully be seeing D23 grace the halls of the Anaheim Convention Center again. As I returned home tired and with a filled to the brim swag bag, I can definitely say that I had a great D23 Expo 2022, and I’m glad to have shared my experience with all of you reading this. Thank you Disney and D23, and as the they said on the Mickey Mouse Club, “see you real soon. Why? Because we like you.”